The Transsituational Influence of Social Norms

Jurnal:

Tolong rujuk ke sumber asli

The Transsituational Influence of Social Norms

Raymond R. Reno, Robert B.

Cialdini, and Carl A. Kallgren

Journal of Personality and

Social Psychology, 1993, Vol.64, No. 1,104-112

Copyright 1993 by the American

Psychological Association Inc

0022-3514/93/S3.00

Three studies examined the behavioral

implications of a conceptual distinction between 2 types of social norms:

descriptive norms, which specify what is typically done in a given setting, and

injunctive norms, which specify what is typically approved in society. Using

the social norm against littering, injunctive norm salience procedures were

more robust in their behavioral impact across situations than were descriptive

norm salience procedures. Focusing Ss on the injunctive norm suppressed

littering regardless of whether the environment was clean or littered (Study 1)

and regardless of whether the environment in which Ss could litter was the same

as or different from that in which the norm was evoked (Studies 2 and 3). The

impact of focusing Ss on the descriptive norm was much less general. Conceptual

implications for a focus theory of normative conduct are discussed along with

practical implications for increasing socially desirable behavior.

Despite

social norms having a history of long and extensive use within the discipline,

there is no current consensus within social psychology about the explanatory

and predictive value of social norms. Whereas social norms have been trumpeted

by some as crucial to a full understanding of human social behavior (e.g.,

Berkowitz, 1972; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975; McKirnan, 1980; Pepitone, 1976;

Sherif, 1936; Staub, 1972; Triandis, 1977), other social psychologists have

suggested that the concept may be vague, overly general, and ill-suited to

empirical study (e.g., Darley & Latane, 1970; Krebs, 1970; Krebs &

Miller, 1985; Marini, 1984). Social psychologists are not alone in their

disillusions concerning social norms. A parallel controversy has developed in

academic sociology, where enthnomethodological and constructionist critics have

faulted the dominant norma-tive paradigm of that discipline (Garfinkel, 1967;

Mehan & Wood, 1975).

Seeking to clarify the role of social

norms, Cialdini, Reno, and Kallgren (1990; Cialdini, Kallgren, & Reno,

1991) distinguished two types. The first of these, descriptive norms, specify what

most people do in a particular situation, and they motivate action by informing

people of what is generally seen as effective or adaptive behavior there.

Injunctive norms, on the other hand, specify what people approve and disapprove

within the culture and motivate action by promising social sanctions for

normative or counternormative conduct. Which of these two types of norms is

focal (i.e., salient) at a particular time will direct an individual's immediate

behavior, according to Cialdini et al.

In

a series of studies that examined the problem of litter in public places,

Cialdini et al. (1990) increased focus on the descriptive norm by having a

confederate litter in front of subjects.

Contrary to simple imitation or

modeling predictions, but in line with Cialdini et al.'s norm-focus theory,

subjects littered less after witnessing the confederate litter if the

descriptive norm of the situation was to not litter (i.e., if the setting was clean).

The fact that the littering rate of subjects who witnessed the confederate

litter in a clean environment was lower than the control rate of littering was

seen as support for the norm-focus model. Simply increasing salience that most

others had not littered in the environment decreased littering, even when this was

accomplished by exposing subjects to a counternormative act.

Even though these studies demonstrated

that focusing subjects on a descriptive norm can result in prosocial behavior,

the successful use of descriptive norm salience techniques appears limited to

settings in which antisocial behavior is not much of a problem. That is,

Cialdini et al. (1990) found that littering was reduced only when the

descriptive norm was made salient in a clean environment. When the descriptive

norm was made salient in littered environments (once again, by focusing

subjects on what others had done there) littering increased above control levels.

Consequently, although the demonstration of these effects was important for

validating the norm-focus theory, the practical utility of such descriptive

norm manipulations for reducing antisocial behavior seems limited.

Fortunately, however, there are

conceptual reasons for believing in the greater utility of injunctive norm

activation. An active, injunctive norm focus should have a pair of socially

desirable effects in settings characterized by socially undesirable action.

First, it should cause a shift of attention away from evidence that antisocial

behavior constitutes the descriptive norm for the setting. Second, it should

lead individuals to attend to a motivational construct—social approval and

disapproval—that directs behavior in a socially desirable direction regardless

of what others may have done in the setting. The potentially beneficial impact

of such a shift in attention focus is suggested by the results of research

indicating that moving a person's attention to a specific source of information

or motivation will change the person's responses in ways that are congruent

with the features of the now more prominent source (Agostinelli, Sherman,

Fazio, & Hearst, 1986; Kallgren & Wood, 1986; Millar & Tesser,

1989; Storms, 1973). To test OUT reasoning in this regard, we chose the norm

regarding littering in public places, as it afforded an instance of a clearly

felt and widely held injunctive social norm (Berkowitz, 1972; Heberlein, 1971)

in our culture. Moreover, attention to the descriptive and injunctive aspects

of the littering norm could be fairly easily manipulated.

Study

1

Study

1

To make the injunctive norm salient in

the present series of studies, a confederate picked up a piece of litter in

full view of our subjects. This manipulation was designed to communicate the

confederate's objection to others' littering; as such, it incorporated the

fundamental motivational component of injunctive norms: social approval and

disapproval. The descriptive norm was made salient in the same manner used by

Cialdini et al. (1990) in prior studies: The confederate littered in the

environment, thereby drawing attention to its littered or unlittered condition

and to the fundamental motivational component of descriptive norms: the

responses of most others in the situation.

In addition, a control treatment was

included in which the confederate merely walked by subjects to provide a

constant amount of social contact. As in previous studies, the environment was

prepared to be either clean or littered.

We had two main predictions: First, we

expected that making the descriptive norm salient would be a successful litter reduction

tactic only when the environment was clean. But, we expected, second, that

making the injunctive norm salient would successfully reduce littering in both

littered and unlittered environments. Finding this latter pattern would support

our belief that an injunctive norm focus is effective in reducing undesirable

behavior even in settings where a negative descriptive norm exists. Such a

result would illustrate the advantage of Cialdini et al.'s (1990) distinction

between injunctive and descriptive norms—the ability to make clear differential

predictions based on injunctive and descriptive norms. Furthermore, because the

application of the norm-focus model to problem behaviors relies on the

effectiveness of the injunctive norm focus in such negative settings, a clear

demonstration of this effect was viewed as important.

Method

Subjects

Subjects were 173 (75 female and 98

male) visitors to a municipal library who were returning to their cars in an

adjacent parking lot during the daylight hours. The age of subjects ranged from

the midteens to the early 70s, with 90% between 20 and 50 years of age.

Procedure

Norm salience. As subjects neared the

parking lot, they encountered an experimental confederate of college age

walking toward them.

In approximately one third of the

instances, the confederate carried a bag from a fast food restaurant, which he

or she dropped into the environment approximately 4.5 m (5 yd) before passing

the subjects; this constituted the throw-down (descriptive norm salient)

condition in which subjects' attention was drawn either to the clean or

littered state of the environment. In another third of the instances, the

confederate was not carrying anything but rather picked up the fast food bag approximately

4.5 m in front of the subject; this constituted the pickup (injunctive norm

salient) condition in which subjects' attention was drawn to social disapproval

of littering. In the final third of the instances, a confederate merely walked

by the subject so as to provide a similar degree of social contact; this

constituted the walk-by (control) condition. A second confederate judged

whether a subject had noticed the littering incident and consequently had

deflected his or her attention at least momentarily to the parking lot floor,

or whether subjects had noticed the confederate pick up the bag. This procedure

allowed us to eliminate a priori the data of subjects who had not experienced the

experimental manipulation.

Existing state of the environment. For

some of the subjects, the parking lot had been heavily littered by the

experimenters with an assortment of handbills, candy wrappers, cigarette butts,

and paper cups; this constituted the littered environment (existing

prolittering norm) condition. For the remaining subjects, the area had been

cleaned of all litter; this constituted the clean environment (existing

antilittering norm) condition.

Measurement of littering. On arriving

at their cars, subjects encountered a large handbill that was tucked under the

driver's side wind-shield wiper so as to partially obscure vision from the

driver's seat. The handbill carried a stenciled message that read, "This

is automotive safety week. Please drive carefully." A similar handbill had

been placed on all other cars in the area as well. From a hidden vantage point,

an experimenter noted whether the driver littered the handbill. Littering was

defined as depositing the handbill in the environment outside of the vehicle.

Because there were no trash receptacles in the area, all subjects who failed to

litter did so by taking and retaining the handbill inside their vehicles before

driving away. In addition to recording the subjects' behavior, this

experimenter also recorded the gender of the drivers because gender differences

in littering have been noted in past research (see Geller, Winett, &

Everett, 1982, for a review).

Analyses

The analyses in this and subsequent

studies were conducted using the SPSS-X log-linear program, wherein tests for

effects within dichotomous data are examined through the nesting of

hierarchical models.

This technique allows the testing of

individual parameters by comparing the differences in the likelihood ratio

chi-square of a pair of nested models. The difference likelihood ratio is

reported as a chi-square.

Results

and Discussion

Although gender was not a variable of

theoretical interest to us, we sought to account for and control for its

influence when possible. Therefore, in addition to our theoretical hypotheses, we

explored the data for gender differences. To do this, a log-linear model that

included gender, norm-salience, and environmental conditions was tested first.

In this model, there was a marginal tendency for women (13.33%) to litter less

than men (28.57%), x2 (l, N= 173) = 3.34, p < .068. Gender did

not inter act with the experimental variables, however. Thus, it was not included

in further analyses.

Our overall expectation was that an

injunctive norm focus would reduce littering regardless of the state of the

environment but that a descriptive norm focus would suppress littering only

when the environment was clean. Looked at another way, we expected that (a) in

the clean environment, both injunctive and descriptive norm-salience procedures

would result in littering rates below control levels; but (b) in the littered

environment, only the injunctive norm-salience procedure would do so.

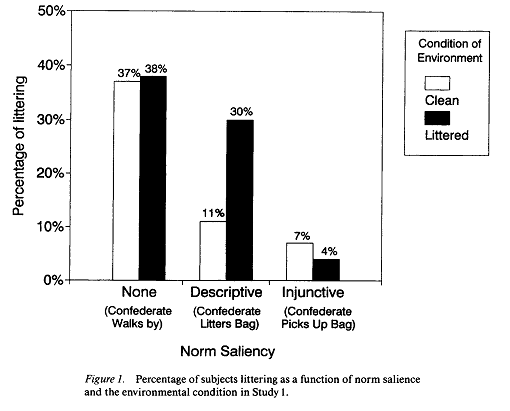

To test our predictions, we conducted a

series of planned comparisons on the littering rates depicted in Figure 1.

First, we tested our prediction within the clean environment condition with a

contrast showing that the combined littering rate of the injunctive (7%) and

the descriptive (11 %) norm-salience conditions was significantly lower than

that of the relevant control (37%)

condition, (l, N= 85) = 9.54, p < .01. Next, we tested x2

our prediction within the littered

environment condition with a pair of orthogonal contrasts demonstrating that,

although the littering rates of the descriptive norm-salience condition (30%) and

its relevant control condition (38%) did not differ (x2 < 1), their

combination was significantly greater than the rate of the injunctive

norm-salience condition (4%), x 2 (l, iV= 90) = 11.40, p < .01.

Finally, we examined our overall expectation in an omnibus contrast that combined

our two predictions by comparing the three conditions we hypothesized to show

higher littering rates (the throw-down and littered environment condition plus

the two walk-by control conditions) against the remaining three conditions,

which were hypothesized to show reduced rates of littering; the difference,

35.2% versus 7.4%, was again clearly significant, x 2 0, N = 173) =

21.21, p< .01.

The pattern of results supported the

predictions made from the norm focus theory. When an antilittering norm

(injunctive or descriptive) was made salient, littering rates were decreased from

control conditions or from conditions in which a prolittering descriptive norm

was made salient (the throw-down and littered environment condition). The alert

reader may notice that subjects who witnessed the confederate throw down a bag in

the littered environment did not litter at rates greater than the control

conditions, as had been demonstrated by Cialdini et al. (1990). Although at

first glance, this apparent failure of replication may be disconcerting, it may

actually point to a limitation on the generality of the descriptive norm's

influence. In the previous research (Cialdini et al., 1990), after witnessing a

confederate dispose of a flyer in a littered environment, subjects were more

likely than control subjects to also litter a flyer. The confederate's behavior

was quite informative about what the subjects should do with the flyers. This

was less the case in the present study. The confederate threw down a paper bag,

not a flyer that was similar to that which the subjects would have the opportunity

to litter. Thus the confederate's behavior in the present study was less

informative to the subjects concerning the descriptive norm. As a result, the

littering rates of subjects in this condition were similar to those of the

control subjects.

Effects related to injunctive norms

were quite provocative from an applied standpoint. Salient injunctive norms

resulted in decreases in littering regardless of the environment's status.

This suggests that injunctive norm

activation procedures can be valuable tools in the amelioration of socially

undesirable behavior; even in settings where these undesirable behaviors predominate

(e.g., fully littered environments, roads where most drivers speed, or

political precincts with low voter turnout). These findings provide a

conceptual replication of the findings of Cialdini et al. (1990) and a clearer

demonstration of the greater trans-situational influence of injunctive norms

relative to descriptive norms.

However, the advantage of an injunctive

norm focus may not be limited to settings characterized by socially undesirable

behaviors. That advantage may apply, as well, to the likelihood of normative

conduct in settings that are different from the one in which the relevant norm

was evoked. Because the injunctive social norms of a culture typically apply to

most settings of that culture, an activated injunctive norm should continue to

direct behavior—provided that it remains salient—in a novel, second setting.

Study 2 offers a test of this possibility.

Study

2

If we are correct that an injunctive

norm focus should transcend situational boundaries, we should expect that such

a focus would lead to reduced littering even in environments other than the one

in which the focus was evoked. To test this hypothesis, we conducted a second

experiment in which the injunctive norms focus and control manipulations from

Study 1 were implemented in two separate environments. The first environment

was a parking lot similar to that used in Study 1. The second environment was a

pathway along a grassy area that was separated from the parking lot. Both

environments were clean.

Consequently the descriptive norm was

held constant across both settings. We hypothesized that when subjects were

focused on the injunctive antilittering norm, they would litter less than control

subjects, regardless of whether the injunctive focus had been created in an

environment that was the same or different from the one where they would have

the opportunity to litter.

Method

Subjects

Subjects were 137 (75 female and 62

male) patrons at a municipal library who were returning to their cars in an

adjacent parking lot during the daylight hours. Subjects' ages were estimated

to range between 16 and 70, with 92% estimated to be between 20 and 60 years of

age.

Procedure

Norm salience. Between leaving the

library and entering the parking lot, subjects encountered an experimental

confederate of college age. As this confederate walked toward the subject, the

confederate either picked up a crumpled fast food bag that was lying on the

ground (injunctive norm salient condition) or simply walked by subjects (control

condition). A second confederate judged whether subjects noticed the

confederate picking up the bag. As in Study 1, these judgments allowed us to

make an a priori determination of which subjects experienced the experimental

manipulation and, consequently, which data should be retained for analysis.

Same versus different environment. Subjects

encountered the confederate in one of two settings. For some subjects, the

procedure was the same as in Study 1: Subjects encountered the confederate as

they were entering and the confederate was leaving the parking lot where

subjects would have a chance to litter (same-environment condition). The

remainder of the subjects encountered the confederate along a path within a

grassy, landscaped section of the property (different environment condition)

that was separated from the parking lot by a brick wall. Because we were

interested only in the impact of the injunctive norm, both the parking lot and

the pathway had been cleaned of visible litter to hold the descriptive norm

constant.

Measurement of littering. Both the

procedures for providing subjects an opportunity to litter and the procedures

for recording their actions were identical to those of Study 1.

Results

and Discussion

As in Study 1, we first estimated a

model that included gender to determine whether differences in littering rates

were due to subject gender. The difference in the littering rates of women (12%)

and men (19.35%) was not statistically significant, nor did gender interact

with norm salience or environmental conditions. Thus, it was not included in

further analyses.

Examination of Figure 2, which depicts

the percentage of litterers in each condition of Study 2, reveals the predicted

pattern. Only one significant effect emerged—the main effect for norm salience;

subjects for whom the injunctive norm against littering was made salient

littered less than control-condition subjects (6.7% vs. 22%), x 2 (l,

N= 137) = 5.48, p < .01. Neither the main effect for type of environment

nor, more importantly, its interaction with norm salience approached significance

(x2 s < 1). Thus, witnessing another pick up litter reduced

littering tendencies in our subjects regardless of whether their observation of

this act of social disapproval occurred in the same setting as or in a

different setting from their opportunity to litter.

These results, when coupled with those

from Study 1, are encouraging with regard to the influence of salient

injunctive norms on behavior. First, an injunctive norm focus appears to be

effective in those situations where behavior change is most needed (e.g.,

littered environments). Second, it does not appear necessary to create this

injunctive norm focus within the particular environment in which abatement of

negative behavior is desired. It is this latter finding that may be of most

practical significance to those interested in modifying behavior by creating an

injunctive norm focus. That increasing injunctive norm salience in one

environment reduced littering in a second environment enhances the potential

practical utility of such an approach.

This finding also has theoretical

import for norm-focus theory. It highlights one of the major conceptual

differences between a descriptive and an injunctive norm focus. That

distinction is explored further in Study 3.

Study

3

Examination of Cialdini et al.'s (1990)

conceptualization of the differences between descriptive and injunctive norms shows

why the utility of these two types of social norms may vary across a variety of

situations. Descriptive norms appear to be more situation-specific in the

information they provide.

That is, descriptive norms communicate

what others have felt to be appropriate behavior in that setting. Consequently,

the influence of such norms may weaken precipitously as individuals move out of

the environment in which the norms were made salient. This may be particularly

true if the environments differ along a dimension related to the behavior in

question.

Injunctive norms, on the other hand,

involve perceptions of what is approved conduct within the culture in general,

which should have substantial cross-situational relevance. That is, descriptive

norms are designed to tell us what makes for adaptive or effective behavior,

which can be influenced and changed by many situation-based factors. But,

injunctive norms are designed to tell us what others have been socialized to

approve and disapprove in the culture, which is likely to change relatively

little from situation to situation; consequently, their influence should

transcend environments.

This point, however, has not been

confidently established by the data presented thus far. In Study 1, as the

environmental conditions changed so did the descriptive norm; thus, it was not possible

to evaluate the trans-situational influence of descriptive norms. Similarly,

because Study 2 did not include a descriptive norm-focus manipulation, the

issue could not be investigated. Therefore, a third study was conducted to test

this component of the norm-focus model, as well as to replicate the results of

Study 2 with regard to the influence of the activated injunctive norm.

We conducted Study 3 in the same

environments that were used in Study 2. If, as we have suggested, descriptive

norms primarily communicate what is typically done within a specific environment,

then littering rates should drop principally where an antilittering descriptive

norm is made salient and not in relatively different environments. In contrast,

as was found in Study 2, making the more general injunctive norm against littering

salient in one setting should have the effect of reducing litter in similar and

different settings. In summary, then, we expected decreased littering (compared

with control conditions) whenever the injunctive antilittering norm was activated,

but we expected decreased littering when the descriptive antilittering norm was

activated only if the opportunity to litter occurred in the same setting as the

norm activation.

Method

Subjects

Subjects were 131 (62 female and 69

male) visitors to a municipal library who were returning to their cars in an

adjacent parking lot during the daylight hours. Subjects' estimated ages ranged

between 16 and 70 years, with 90% ranging between 20 and 50 years.

Procedure

Norm salience. Between exiting the

library and entering the parking lot, subjects encountered an experimental

confederate of college age.

In all conditions, the library grounds

and parking lot had been cleaned of visible litter. The confederate's behavior

was scripted to make salient either the descriptive or injunctive antilittering

norm or to provide no normative information (control). The descriptive

norm-salience manipulation differed from that used in Study 1. In the present

study, subjects in the descriptive norm condition witnessed a confederate dispose

of a fast food bag he or she was carrying by throwing it into a nearly full

trash receptacle approximately 4.5 m (5 yd) before passing the subject.

Although this receptacle was present in all conditions, we reasoned that the

confederate's act of throwing litter into it would bring a subject's attention

to evidence of what most people did with regard to litter in that particular

(clean) setting—that is, that they refrained from disposing of trash improperly

there. To increase injunctive norm salience, we relied on the manipulation we

had used successfully in Studies 1 and 2: Subjects saw a confederate who, after

passing the earlier described trash receptacle, encountered a discarded fast

food bag, picked it up, and carried it away in the direction of the library.

Same-different environment. Subjects

encountered the confederate in one or the other of the two settings used in

Study 2. Due to the method by which the descriptive norm was to be activated in

the present study, it was necessary to place a trash receptacle in each of the

two settings. These receptacles were present in both settings for subjects in all

conditions of the experiment. However, because the placement of the receptacles

in both settings made it inconvenient, no subjects used a receptacle to dispose

of their fliers.

Measurement of littering. Both the

procedures for providing subjects an opportunity to litter and for recording

their actions were identical to those of the prior two studies.

Results

As in the previous two studies, we

screened for any gender differences in littering. Although women tended to

litter less than men, 16.13% versus 27.54%, this difference was not statistically

significant, x 2 0, N = 131) = 2.465, p > .10, nor did it interact

with our primary independent variables. Thus, gender was not examined in our

subsequent analyses.

The hypothesized effects were tested

through a series of a priori contrasts. The main hypothesis was that subjects'

littering would be reduced from control levels wherever (parking lot or

pathway) the injunctive norm against it was made salient or when the

descriptive norm against littering was made salient in the parking lot

(same-environment condition). However, no such reduction was predicted when the

descriptive norm against littering was made salient in an environment different

from the parking lot (i.e., the pathway). Looked at in another way, we expected

that (a) in the same-environment condition, both the injunctive and descriptive

norm-salience procedures would suppress littering relative to control levels,

but (b) in the different-environment condition, only the injunctive norm-salience-lience

procedure would do so.

Figure 3 depicts the littering rates

for each of the experimental conditions and shows a pattern of data that is

congruent with our hypotheses. First, we tested our prediction within the same

environment condition with a simple contrast demonstrating that the combination

of the littering rates in the injunctive (13%) and the descriptive (17%)

norm-salience conditions was lower than that of the relevant control (32%)

condition, x 2 (l, #= 9i) =

3.55, p < .06. Next, we tested our prediction within the different

environment with a pair of orthogonal contrasts demonstrating that, although

the littering rates of the descriptive norm-salience condition (36%) and its

relevant control condition (33%) did not differ from one another (x2

< 1), their combination did differ significantly from the lower rate of the injunctive

norm-focus condition (0%), x2 (l, N=A0) = 7.62, p < .01. Finally,

we tested the interaction form of our overall prediction with an omnibus

contrast. The predicted interaction was assessed by combining the two

injunctive norm-salience conditions with the descriptive

norm-salience-same-environment condition and comparing them with the combined

control conditions plus the descriptive norm-salience-different-environment

condition. This contrast generated clear support for the overall prediction, x2

(l, N = 131) = 8.14, p < .01.

Discussion

Interpretations

of the Data

The results of the present study

further support the practical advantage of focusing individuals on injunctive

versus descriptive norms. An injunctive norm focus proved decidedly more robust

in its impact across situations than a descriptive norm focus. Subjects who saw

another refrain from littering were affected by that display only in that

particular setting. On the other hand, subjects who witnessed evident social

disapproval of another's littering were affected by that display in a rather different

setting as well. According to the norm focus theory, this was the case because

(a) subjects were focused by the re-specie displays either on the descriptive

norm or on the injunctive norm, and (b) the effect of focusing on the

injunctive norm is more likely to transcend situational boundaries, be-cause

the injunctive norm orients individuals away from a concern about how others

have behaved in a particular setting and toward a concern about what others

approve or disapprove of across the culture.

A secondary benefit of the obtained

pattern of results of Study 3 is that it provides evidence against an

alternative explanation for the findings of the first two studies. That is, it

might be argued that the conditions that produced the lowest littering rates in

those earlier experiments were the conditions that made the confederate's

litter-related behavior most salient to subjects. Take, for example, the

procedures of Study 1. It is conceivable that a confederate who littered into a

clean environment or a confederate who picked up litter in either a clean or a littered

environment was a more distinctive litter-related stimulus than a confederate

in the other three conditions of that experiment. Similarly, a confederate who

picked up litter in Study 2 may well have become a more salient litter-related stimulus

than a confederate who simply walked past subjects. Thus the outcomes of those

two studies could be explained as due to subjects' negative reactions to the

concept of littering whenever that concept was made prominent for them.

However, such an account cannot readily explain the pattern of data in Study 3,

where subjects who saw a confederate dispose of a bag in a parking lot

(same-environment condition) littered less than those who saw the confederate

dispose of a bag in a different environment. The confederate's behavior should

have been no more salient or more positive in either environment. One might argue

that the saliency of the manipulation may decay over time. This line of thought

accounts for the pattern of data for the trash can (descriptive norm) condition

but fails to predict the observed pattern of data in the pickup (injunctive

norm) condition of Study 3. Consequently, it is more difficult for this alternative

theory to explain the results from all three studies.

A closer look at Study 3 reveals the

important role of social sanctions in distinguishing between the effectiveness

of injunctive and descriptive norms. After all, subjects in both conditions saw

another person perform a behavior in a particular setting from which they could

have reasonably inferred the other's disapproval of littering. Yet, it was only

when the confederate picked up another's litter that littering was generally

re-diced. We think this was so because of the idea of social sanctions that is

associated with injunctive norms. The behavior of the confederate who picked up

another's litter was unambiguous as to its interpersonal message. It

communicated that the confederate disapproved of and found littering by others (our

subjects included) objectionable. In this way, subjects were focused on

potential social sanctions, the central feature of in-juncture norms, which

increased their awareness of the society-wide rule against littering. In

contrast, subjects who saw litter thrown into a receptacle got a different

message from the con-federate, that is, "I find littering objectionable

within my own behavior," which did not remind them directly of social sanctions

or, consequently, of injunctive norms. Instead, subjects may have remained

focused on the descriptive norm of what another and similar others had done in

that setting.

Although such interpretations fit well

with the data, it should be recognized that they are not based on any direct

evidence that the experimental procedures designed to focus subjects differentially

on descriptive and injunctive norms had the in-tended effects. Because of the

field character of the reported studies, it was not possible to administer

manipulation checks or measures of mediating cognitive processes, as can be

done in traditional laboratory research. A critic could fairly contend, then,

that confident interpretation of the present three studies in terms of

norm-focus theory requires another step. It remains to be demonstrated that the

experimental operations we have used to focus subjects differentially on

descriptive and injunctive norms are indeed effective in doing so.

Tests of Norm-Focus Inductions

To provide such a demonstration, we

conducted a separate study on 70 undergraduate psychology course students at

Arizona State University. Each student received a questionnaire describing the

scene encountered by the subjects in each of the three experimental conditions

of the present research. Thus, the students were asked to read and picture the

following scenes (presented in a random order):

A college-age individual who is walking

on the grounds of a local municipal library discards a paper bag by throwing it

into a trash barrel, and then walks on [descriptive norm induction].

A college-age individual who is walking on the grounds of a

local municipal library discards a paper bag by throwing it on the ground, and

then walks on [descriptive norm induction].

A college-age individual who is walking on the grounds of a

local municipal library picks up a discarded paper bag from the ground and

throws it into a trash barrel, then walks on [injunctive norm induction].

The students were then asked to indicate whether, when they pictured

the scene, it focused them more on (a) the extent to which other people do and

do not litter [descriptive norm] or (b) the extent to which other people

approve and disapprove of littering [injunctive norm].

The students' responses offered good

support for the validity of our norm-focus procedures. Picturing an individual

who discarded a paper bag by throwing it in a trash barrel led the great majority

of students to focus predominantly on the descriptive norm, that is, "the

extent to which other people do and do not litter," rather than on the

injunctive norm (87.2% vs. 12.8%, z = 12.48, p < .01). The same was true

when students pictured an individual who threw down a paper bag (70% vs. 30%, z

= 8.37, p < .01). However, picturing an individual who picked up a paper bag

led the great majority of students to focus predominantly on the injunctive

norm, that is, "the extent to which other people approve and disapprove of

littering," rather than on the descriptive norm (91.4% vs. 8.6%, z =

13.48, p < .01).

Analyzing these data further by McNamara’s

chi-square test for dependent samples with a Bonferroni correction showed that the

relative proportions produced by the injunctive norm-focus induction were

clearly different from either of those of the two descriptive norm-focus

inductions, McNemar x2 s(l, N = 70) = 55.00 and 43.00, respectively,

both ps < .001. The relative proportions of the two descriptive norm

inductions were not different at conventional levels by this test when

controlling for Type I error; they were marginally different, however, McNemar

x2 (l, N = 70) = 5.538, p < .019; statistical significance using

the Bonferroni correction requires a = .05/3 = .016.

Thus, the results of the questionnaire

study support well our assumptions concerning which norm, descriptive or

injunctive, our experimental procedures made salient for the subjects in our

field experiments. Consequently, our confidence is heightened that the

norm-focus theory provides an apt interpretation of the data from the three

field studies reported here as well as from the field studies reported by

Cialdini et al. (1990), which used similar experimental procedures.

General

Discussion

A set of predictions based on a

norm-focus theory (Cialdini et al., 1990) was tested in a series of three

studies. The data patterns from these three studies converge to allow four main

conclusions that further clarify the distinction Cialdini et al. made between

injunctive and descriptive norms. First, despite existing skepticism and

criticism of normative explanations, the present data support the viability of

social norms as powerful behavioral directives, consistent with Cialdini et

al.'s findings. Second, at least two distinct types of social norms are effective

in this regard: social norms of the descriptive kind, which guide one's

behavior through the perception of how most others would or do behave; and

social norms of the injunctive kind, which guide one's behavior through the

perception of how most others would sanction one's conduct. Third, in contrast

to descriptive norms, injunctive norms can increase prosocial action even in

settings characterized by antisocial behavior. Finally, an injunctive norm

focus enhances norm-congruent responding in environments similar to and

different from those in which the focus occurred; descriptive social norms, on

the other hand, seem only to influence behavior in the environments where they

are made focal.

Although we argue for a norm-focus

model, we do not discard the previous criticisms against normative explanations

of behavior (e.g., Darley & Latane, 1970; Krebs, 1970). These criticisms

underline the components from which the norm-focus model draws its power.

According to our theory, one cannot think of norms in a general or vague sense.

Rather one needs to specify clearly the type of social norm (injunctive or

descriptive) at work and guarantee that it will be focal before one can feel confident

in normative accounts of behavior change. In all three of our studies, for

example, both descriptive and injunctive norms were present within each of the

environments where control subjects were acting. Yet, it was not until a

confederate's action made these norms focal that it was possible to appreciate the

magnitude of their power to guide human conduct.

In addition to demonstrating the

effects of norm focus, the data, particularly from Study 3, identified the main

motivational component of injunctive social norms: social sanctions.

In this regard, it appears that the

concept of approval and disapproval needs to be sharpened in its relation to

social norms.

Witnessing another approve or

disapprove of norm-related responding may only engage the full power of the

relevant injunctive social norm when the observer is made to think that such approval

or disapproval applies to his or her relevant conduct.

Expressing disapproval for

counternormative behavior in one's own actions by visibly refraining from the

action should not bring to bear on observers the full salutary impact of the

injunctive social norm. Rather, this impact should flow from witnessing visible

expression in others of disapproval of counternormative action. Thus, a key to

the effective activation of injunctive social norms is a focus on the

applicability of interpersonal sanctions to the behavior in question.

This is not to say that we think

injunctive social norms function only when evaluating others are physically present

to provide social sanctions. We concur with the developers (Cooley,1902; Mead,

1934) and modern proponents (e.g., Schlenker, 1980) of symbolic interaction

theory that people often seek to satisfy the expectations of imagined

audiences, one of which the generalized other—represents the generalized

viewpoint of society. Thus, it is our view that once focused on a representative

of society who approves or disapproves of another's behavior; an observer is

likely to conform to the societal rules for that behavior even when alone, as

long as the focus remains.

From a practical standpoint, these

distinctions between injunctive and descriptive social norms should be of

value, particularly to those interested in enhancing the likelihood of socially

beneficial behavior through norm activation. Such individuals would be best

advised under most circumstances to use procedures that activate injunctive social

norms. Once activated, injunctive norms are likely to lead to beneficial social

conduct across the greatest number of settings. Activating a descriptive social

norm, on the other hand, is only likely to lead to socially desirable behavior

in settings where most individuals already behave in a socially desirable

manner.

As with most research domains, worthy

additional questions remain to be answered. For instance, further research

should examine the nature of stimuli that are likely to lead to a norm's salience.

Likely candidates for investigation in this regard are certain factors related

to the norm itself such as its cognitive accessibility, its recency and

frequency of prior activation, and its degree of connectedness with other

salient norms in the environment. In addition, Schwartz (1973, 1977; Schwartz

& Howard, 1982) has argued persuasively that individuals possess personal

norms, that is, self-based standards for conduct that flow from internalized

values. The extent to which a heightened personal norm would affect the

salience of injunctive or descriptive social norms is yet unexplored. The

answers to these questions would further enhance our conceptual understanding

of the influence of social norms, as well as sharpen our ability to use them in

applied settings.

References

Agostinelli, G., Sherman, S. J., Fazio, R. H., & Hearst,

E. S. (1986).

Detecting and identifying change: Additions versus

deletions. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance

12, 445-454.

Berkowitz, L. (1972). Social norms, feelings, and other

factors affectinghelping and altruism. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in

experimental social psychology (\o\. 6, pp. 63-108). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Cialdini, R. B., Kallgren, C. A., & Reno, R. R. (1991).

A focus theory of normative conduct. Advances in Experimental Social

Psychology, 24, 201-234.

Cialdini, R. B., Reno, R. R., & Kallgren, C. A. (1990).

A focus theory of

normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce

littering in public places. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 1015-1026.

Cooley, C. H. (1902). Human nature and the social order. New

York:Scribners.

Darley, J. M., & Latane, B. (1970). Norms and normative

behavior:Field studies of social interdependence. In J. Macaulay & L. Berkowitz

(Eds.), Altruism and helping behavior (pp. 83-102). San Diego,CA: Academic

Press.

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude,

intention, and behavio Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Garfinkel, H. (1967). Studies in elhnomethodology. Englewood

Cliffs,NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Geller, E. S., Winett, S., & Everett, P. B. (1982).

Preserving the environment. New "Vbrk: Pergamon Press.

Heberlein, T. A. (1971). Moral norms, threatened sanctions,

and littering behavior. Dissertation Abstracts International, 32, 5906A. (University

Microfilms No. 72-2639)

Kallgren, C. A., & Wood, W W (1986). Access to

attitude-relevant information in memory as a determinant of attitude-behavior

consistency. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 22, 328-338.

Krebs, D. L. (1970). Altruism: An examination of the concept

and a review of the literature. Psychological Bulletin, 73, 258-302.

Krebs, D. L., & Miller, D. T. (1985). Altruism and

aggression. In G. Lindzey & E. Aronson (Eds), The handbook of social psychology

(3rd ed, Vol. 2, pp. 1-71). New York: Random House.

Marini, M. M. (1984). Age and sequencing norms in the

transition to adulthood. Social Forces, 63, 229-244.

McKirnan, D. J. (1980). The conceptualization of deviance: A

conceptualization and initial test of a model of social norms. European Journal

of Social Psychology, 10, 79-93.

Mead, G. H. (1934). Mind, self and society. Chicago:

University of Chicago Press.

Mehan, H., & Wood, H. (1975). Reality of

ethnomethodology. New York: Wiley.

Millar, M. G, & Tesser, A. (1989). The effects of

affective-cognitive consistency and thought on the attitude-behavior relation.

Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 25,189-202.

Pepitone, A. (1976). Toward a normative and comparative

biocultural social psychology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

34, 641-653.

Schlenker, B. R. (1980). Impression management. Monterey,

CA: Brooks-Cole.

Schwartz, S. H. (1973). Normative explanations of helping

behavior: A . critique, proposal, and empirical test. Journal of Experimental

Social Psychology, 9, 349-364.

Schwartz, S. H. (1977). Normative influences on altruism. In

L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 10, pp. 221-279).

San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Schwartz, S. H., & Howard, J. A. (1982). Helping and

cooperation: A self-based motivational model. In V Derlega & H. Grezlak

(Eds.), Cooperation and helping behavior (pp. 83-98). San Diego, CA: Academic

Press.

Sherif, M. (1936). The psychology of social norms. New York:

Harper.

Staub, E. (1972). Instigation to goodness: The role of

social norms and interpersonal influence. Journal of Social Issues, 28,131-150.

Storms, M. D. (1973). Videotape and the attribution process:

Reversing actors' and observers' points of view. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 27, 165-175.

Triandis, H. C. (1977). Interpersonal behavior. Monterey,

CA: Brooks/Cole.

Catatan:

Raymond R. Reno, Department of Psychology, University of

Notre Dame; Robert B. Cialdini, Department of Psychology, Arizona State University;

Carl A. Kallgren, Department of Psychology, Pennsylvania State University,

Behrend College.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed

to Raymond R. Reno, Department of Psychology, University of Notre Dame, Notre

Dame, Indiana 46556.

Komentar

Posting Komentar