The Help Phase

The Help Phase:

Intervention

INTRODUCTION

Once the factors causing the outcome variable

have been identified and mapped in the process model, the intervention can be

developed. An intervention is a means to change the causal factors and thus the outcome variables in the desired

direction. An adequate intervention targets

one or more causal factors in the process model. Yet often it is not feasible or even necessary to target all variables

in this model. Therefore, the first step in the Help stage of the PATH model is to determine which causal factors

will be targeted in the intervention.

The modifiability of the factors and the expected effect sizes of interventions will direct this choice. Once

these factors have been identified, an intervention

that targets these factors can be developed. Decisions must be made about how the target group will be reached and what the

content of the intervention will be. The

content depends largely on empirical evidence. The last step in the Help phase

concerns the implementation process.

Here care is taken that the intervention is used as intended. We want to emphasize that the present

chapter only gives an introduction into the art of intervention development,

and that more detailed approaches are available elsewhere, for instance, in the context of health education (see for

example, Bartholomew, Parcel, Kok

& Gottlieb, 2006).

It is

known that racial discrimination may have severe psychological consequences for people who are discriminated against: they

may feel unfairly treated, depressed, angry and/or sad. But can racial

discrimination also harm physical health?

In general Black US citizens suffer from higher blood pressure than White US

citizens. Is it possible that this has something to do with racial

discrimination? To answer this

question, researchers Nancy Krieger and Stephen Sidney conducted a study*

among more than 4000 Black and White adults. Participants' blood pressure was assessed, and they were asked

about their experiences with racial

discrimination and their ways of coping with it. They were asked, for

Box 5.1 Case Study: Racial Discrimination

and Blood Pressure

and Blood Pressure

The

Help Phase 107

example,

'Do you accept racial discrimination as a fact of life or do you try to do something about it?', and 'Do you talk to other people

about being discriminated against or do you keep it

to yourself?'.

The

researchers discovered that, surprisingly, among working-class Black men and women, blood pressure was elevated among those who

reported either a great deal of racial

discrimination or no discrimination at all.

According to the researchers this does not mean that

(intermediate) levels of racial discrimination are healthy.lt is, for instance, possible that people who experience discrimination

find it too painful to admit to and, consequently, do not report it as such. It

is also possible that discriminated individuals suffer

from so-called 'internalized oppression', that is, they perceive unfair

treatment as 'deserved' and non-discriminatory.

Furthermore,

the researchers found that the way Black individuals cope with racial discrimination is at least as important as racial

discrimination itself. Among working-class Black men

and women blood pressure was highest among those who responded

to unfair treatment by accepting it as a fact of life, and did nothing about

it.

Krieger

and Sidney's (1996) study underlines that racial discrimination is not just a problem for those who are discriminated against, but

for society as a whole. Having high blood pressure

and falling ill as a consequence of feeling discriminated against may lead to job absenteeism, a loss of

productivity and a rise in healthcare

costs. Moreover, the study suggests that, in addition to anti-discrimination policies aiming to prevent discrimination, the government

might also develop a campaign to encourage

Blacks not to accept discrimination as a fact of life but to become assertive and to claim their right to fair

treatment

*

Krieger, N. & Sidney, S. (1996). Racial discrimination and blood pressure:

the CARDIA study of young black and white

adults. American

Journal of Public Health, 86, 1370-1378.

PREPARING INTERVENTION

DEVELOPMENT

The essence of the final Help phase is that

interventions must focus on changing factors

in the explanatory model. It is not always necessary, appropriate, or possible

to target all the factors in the

explanatory model. Therefore, the applied social psychologist chooses the factors that are modifiable and that have the greatest effect on the outcome variable. To do so, it is convenient to put

all the factors from the process model into a balance table (see Table 5.1).

Modifiability

Although presumably many

variables in the selected process model can be influenced, there may be considerable

differences in the degree to which this is possible. Three questions can help to exclude factors that are

difficult to change:

108 Applying Social Psychology

1.

Does the factor concern a

stable personality

trait? For example, when a psychologist wants to

develop an intervention to tackle shyness, one may include introversion as a

personality variable with a high degree of

explanatory power in the model, but this variable has little potential for change outside intensive

psychotherapy. Or when one includes neuroticism as a variable in a model predicting burnout, one needs

to realize that this is a stable personality trait that will be difficult to

change.

2.

Is the factor related to

deeply held political or religious values? For example, it will be virtually impossible to attract attention for a programme on

condom use from people who, based on

their religious convictions, are strongly against premarital sex. Or it may be

difficult to convince selection officers with very negative

attitudes towards immigrants to endorse a policy to employ people from

minority groups.

3.

Is the factor related to stable environmental

conditions? For example, a problem might be that students

do not park their bikes in the appropriate parking spaces at university.

Perhaps they see many other bikes parked in

inappropriate spaces and follow that example. However, this might be due to insufficient bike storage

facilities on campus, which is a stable environmental condition.

Effect

Size

Not all factors in the process model have an

equally strong impact on the outcome variable, and applied psychologists should focus

on the ones that have the strongest effect. This selection is facilitated

if there is empirical evidence for the strength of the causal relationships

in the model. Often, however, this is not available and psychologists

'guestimate' the effect sizes. Various sources of information can be

helpful to estimate the effects.

Past

Experience with Similar Situations

Suppose

a school aims to tackle cultural segregation among their students.

In the

process

model, the recruited psychologist identifies 'knowledge about people from other

cultures' and 'personal contact with people from other cultures' as factors

predicting segregation. Yet last year the school board decided

to provide youngsters with positive knowledge on other cultures, and,

although students were more positive, this seemed to have no effect

on social interactions in the school. Armed with this knowledge,

it does not seem very sensible to try this strategy again.

Empirical

Evidence

For a number of factors in the model, there

may be empirical evidence that they are resilient to change. For example, the

literature shows that most people are unrealistically optimistic about their

lives (Weinstein & Klein, 1996). Most children, for example,

believe they have less risk than the average child of becoming overweight and

developing health problems as a result of being overweight. As this optimism is

a statistical impossibility — it simply cannot be that most

people are better off than the average person — a psychologist may believe it

could help to educate people about this illusion. However, research suggests that

such biased perceptions are hard to correct and that their influence

on behaviour is limited (Weinstein, 2003). Thus, one would not select

this factor to be targeted in an intervention. In general, it makes sense to

look for evidence showing the degree to which the model variables

are changeable.

The

Help Phase 109

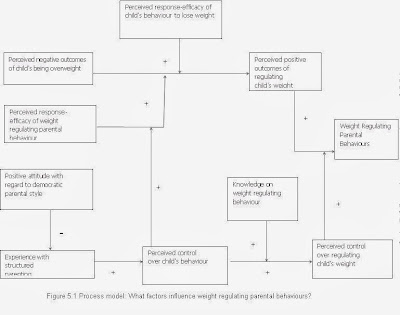

Figure 5.1 Process model: What factors influence weight regulating parental behaviours?

The

Balance Table

A

balance table helps in making the decision on which factors will be targeted in

the intervention. We illustrate the balance table through the

problem of obesity among children in the UK. Britain is one of the 'fattest'

nations in Europe. In 2000, 27 per cent of girls and 20 per

cent of boys aged 2 to 19 years were overweight (see the websites on NationalStatistics,

www.statistics.gov.uk).

Obesity amongst children is a problem of great concern: such children

have a high risk of developing long-term chronic conditions, including

adult-onset diabetes, coronary heart disease, orthopaedic disorders, and

respiratory disease. A social psychologist is asked to develop an intervention

to help tackle this problem. In studying the literature she

discovers that one of the major causes of obesity is the

influence of parents on the weight of their children (Jackson, Mannix &

Faga, 2005), namely, that parents may not do enough to stop weight

gain in their children. Such behaviours are referred to as weight regulating parental behaviours. A

psychologist will develop a process model in which these behaviours

are the outcome variable (see Figure 5.1).

Next, a psychologist will evaluate all the

variables from the process model with regard to their modifiability and their

effect size, that is the magnitude of the impact of the change on the outcome

variable.

110 Applying Social Psychology

Table 5.1 Balance table

Variables from the process model

|

Modifiability

|

Effect

size

|

1.

Perceived negative outcomes of child being

overweight

|

++

|

|

2.

Perceived positive outcomes of weight

reducing parental behaviours

|

++

|

|

3.

Perceived

response-efficacy of child's behaviour to lose

weight (does a change in the child's behaviour lead to

losing weight?)

|

++

|

|

4.

Perceived control over weight reducing

parental behaviours

|

||

5.

Knowledge on weight reducing parental

behaviours

|

++

|

++

|

6.

Perceived control over child's behaviour

|

++

|

|

7.

Experience with structured parenting

|

0

|

|

8.

Positive attitude with regard to democratic

parental style

|

0

|

0

or +

|

Note With regard to modifiability: ++ = high modifiable; + =

medium modifiable; 0 = low modifiable, — = not

modifiable, +/0 = depends on another variable.

With regard to the effect size: ++ = large effect; + =

moderate effect; 0 = small effect; — = no effect +10 = depends on

another variable.

First, she evaluates the modifiability of the

eight causal factors in the process model. The

first three factors — the perceived negative outcomes of a child being

overweight, the perceived positive outcomes of regulating one's

child's weight, the perceived response-efficacy of a child's behaviour to

lose weight — are beliefs based on factual knowledge and on

interpretations of past events or experiences. In general, beliefs can be

influenced quite well. Furthermore, the perceived positive outcomes of weight

regulating parental behaviours can only be brought about under conditions of

sufficient response-efficacy regarding the child's behaviour, that

is, when the parental behaviours produce the desired change in the child's

behaviour. The knowledge about weight regulating parental behaviour, and how to

perform it, can also be modified as it only requires adequate basic

information processing and storage. Structured parenting refers to a

parenting style in which children are actively guided and given clear

directions for choices and behaviours, for example, concerning food

intake and physical exercise. The experience with this type of parenting is

also modifiable and can be changed by practising it. Structured parenting

is less likely the more parents tend to engage in a democratic

parenting style, i.e. have a parenting style in which children are stimulated

(or often just left) to make their own choices. A positive attitude with

regard to a democratic parental style is perhaps difficult to

change as it may be based on parental modelling and a history of

perceived reinforcement of that

style. The conclusions with regard to the factors' modifiability are depicted

in Table 5.1.

Next,

she will evaluate the effect size of the

causal factors in the process model. How strong is the effect on the outcome

variable? Changes in the first three variables in the

balance table are probably possible but their effects on the outcome variable

largely depend on parents' perceived control over regulating

their children's weight. Just changing these variables may have a small

effect as only some parents will have

The

Help Phase 111

sufficient control beliefs. Changing the

knowledge on weight regulating parental behaviour can have a large effect, as it is

a primary condition to engage in such behaviour. Changing the positive attitude with

regard to a democratic parental style has uncertain effects, as it does not guarantee

that an adequate alternative style will be adopted. Changing the perceived control over

the child's behaviour can have large effects as it is a basis for developing

perceived positive outcomes of regulating the weight of one's children and perceived

control over this behaviour. Finally, experience with structured parenting can have various effects but it

does not guarantee that parents are skilled

in the specific behaviours regulating the weight of their children. A psychologist

will summarize her findings in the balance table (see Table 5.1).

From the balance table it appears that an

intervention that targets the knowledge on weight regulating parental behaviour

and the perceived control over a child's behaviour will probably be most successful. In

addition, a psychologist may also target the perceived negative outcomes of a

child being overweight, the perceived positive outcomes of the parental

behaviour, or the perceived response-efficacy of a child's behaviours.

DEVELOPING THE INTERVENTION

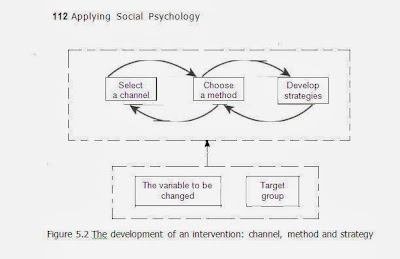

Once the psychologist has decided which variables to target, the

intervention can be developed.

Three tasks can be distinguished in the development of an intervention:

1.

Choosing

the right channel, in which way one may reach the target group

members for example.

2.

Selecting

the appropriate methods, the

way the changes will be brought about, for example, by offering a role model or performing a

skill exercise.

3.

Developing

the strategies, the translation of the methods into concrete aspects of the

intervention. For example, when the method is social modelling, the strategy refers to the exact model and the things the model says and

does.

Developing

the strategies, the translation of the methods into concrete aspects of the

intervention. For example, when the method is social modelling, the strategy refers to the exact model and the things the model says and

does.

The channel, the method and the strategy must consider the target

group for intervention. A social

psychologist may focus on improving patient skill in taking a specific medicine when the target group consists of those

patients who already use, or who will use, that particular medicine. The choice

of channel is guided by the need to reach this target group (for example, through using a pharmacy) and by the method

(for example, modelling: watching another

patient taking the medicine on a DVD). The specific model (strategy) demonstrating the skills depends

upon the target group (for example, using an older model when the

patients are elderly). It is important to note that the development of an intervention is usually a dynamic process: choices for

the channel, the method and the strategy are made in combination (see

Figure 5.2).

The Channel

112 Applying Social Psychology

Figure 5.2 The development of an

intervention: channel, method and strategy

given of various channels and their

characteristics. Channels have several features,

and may vary from simple (for example, sticker or label) to

complex (for example, community intervention), each communicating a

distinct type of information (for example, text, picture) and a

different volume of information (for example, one simple message versus

a complex set of arguments). Some channels communicate with high intensity (say,

group therapy) and others with low intensity (say, information signs).

Channels

also differ in the potential reach of the

target group (see Table 5.2). For example, a label on a product has the

potential to reach all the users of a product, while a radio

message reaches only part of the population of users. In addition, some

channels will only have small effects on the

individual level (say, a sticker), while others can have large effects (the

example of group therapy). Lastly, channels may bring about different types of effects. For example, a label is

appropriate to increase people's knowledge, while counselling is more

appropriate to change complex and deeply rooted behaviours.

The

channel is chosen on the basis of information about the target group, the

relevant variables, methods and strategies. The following issues

should be considered when choosing the channel:

1.

Is the channel an effective way to reach the target

group? (See Table 5.3, potential reach.) When people want to know

how to use a product, say a wrist-exercise tool, using the label on

the tool works better than a television ad. The label ensures that people who

buy the tool have access to the information.

2.

Is exposure through this channel intensive

enough to change the variable? (See Table 5.2, effect

on individual level.) A billboard depicting a young woman during a physical

work-out may remind people that physical exercise is

desired, but may not lead to a change in attitudes toward working-out. Daily

feedback through the internet, however, may shape people's positive experiences with fitness, leading to the

desired changes.

Table 5.2 (Continued)

· CD-Rom/DVD Text,

pictures, sound, video, interaction Depends on the Medium New knowledge/

application2 Psychological change/

Behavioural

change

·

Internet/E-mail Information

sites,

interactive sites, People

with access to Small New

knowledge/

reminder mails, etc the internet Psychological/

change

Behavioural

change

· Cell-phone Reminder calls, SMS People

in the database Small Psychological

or all those who request change/

the service Behavioural

change/Reminder

· Television Commercials, infomercials, People who watch TV Medium New

knowledge/

documentaries, spots, etc channel at the time Psychological

of broadcasting change

· Minimal A few short personal contacts People who are Medium Psychological

counselling referred

to it change/

Behavioural

change

· Extensive Several or many personal contacts of People who are Medium/Large Psychological

counselling about

30-60 minutes referred to it change/Behavioural

change

· Group

training Education

and skills training in a group; People

who are Medium/Large Psychological

mostly 1 to 10 meetings referred

to it change/Behavioural

change

· Group

therapy Applying

therapeutic means to induce People

who are Large Psychological

change in individuals partly by means of referred to it change/Behavioural

Table 5.2 (Continued)

·

Regulations/laws

·

Structural environmental

changes

·

Community' intervention

|

Agreements about

permitted

or banned behaviours in more or

less specified contexts

Changing

the environment to regulate experiences or behaviours, e.g. by regulating the exposure to certain stimuli or

the availability of a specific product Changing peoples' experiences or behaviours by changing the structural and

informational

influences of the community they belong to

|

Depends on the application'

People who

encounter the specific environment

Members of the community

|

Large

Large

Small

|

Behavioural change

Behavioural

New knowledge/ Psychological change/ Behavioural

change

|

A

CD-Rom/DVD can be distributed in many ways. For example, they can be actively

sent to people who are registered in a database, they may be ordered

by those who feel they have a need for it or they can be distributed together

with product X.

3.

Is the channel appropriate for

the method and strategy? A sticker is less appropriate for modelling complex skills, such as learning to lead

a healthier lifestyle, while an interactive DVD gives several possibilities for modelling and practising healthy

skills. (See Table 5.2, effect type.)

The Method

Intervention methods also require consideration. Methods

are often derived from theoretical frameworks. For example, the foot-in-the-door

technique

(Cialdini & Trost, 1998), according to which people more easily accept a major request after first

complying to a minor request, is embedded in the theory

of self-perception that argues that people adjust their attitudes to their

behaviours (Bern, 1972). Such theories are important because they specify the conditions

under which the method is most or least likely to be successful. For example, according to social learning theory, modelling is most

effective when the similarity between model and target individual is high (Bandura, 1986).

From the various theories, phenomena and concepts in the Glossary (pp. 136-47) one can

often deduce ideas about methods.

Selection of a method

depends, first, on consideration of the balance table (see Table 5.1). For each variable,

an intervention method must be chosen. Suppose 'attitudes of police officers towards

foreigners' and 'communication with foreigners' are the selected variables to

improve the treatment of tourists in a city in Spain. Modelling might be used to demonstrate communication

skills, whereas the method of argumentation might target attitude

change. Second, selection of a method depends on the extent to which the method 'fits'

the variable one aims to change. Whereas some channels can motivate people to show

the desired behaviour, they cannot teach them how to change it. For example, it is

easy to arouse fear in smokers through a 30 second television advertisement, but it is

difficult to help them quit smoking using this channel. In contrast, it is

The Help Phase 117

often sufficient to remind people of the benefits of a certain

behaviour by using a prompt. For example, a sign on an elevator

door can prompt people to use the stairs for exercise.

The following methods are frequently used

in psychological interventions.

Goal

Setting

Setting

concrete and specific goals is important. Goals direct people's attention and effort,

provide them with expectations, and give the opportunity for feedback on goal accomplishment,

thereby regulating motivation. Goal setting changes behaviour by defining

goals that people must reach in a given period of time (Locke & Latham, 2002).

For instance, as regards being overweight, a goal can be set in terms of weight

loss in kilos over a particular time period. Sub-goals can help people

work on small, but important, steps in reaching the superordinate goal.

For example, in patients who have had a stroke, a goal in the

rehabilitation could be: 'After three months I can walk 200

metres by myself'. Many studies support the effectiveness of goal setting.

Evans and Hardy (2002) examined the effects of a five-week

goal-setting intervention for the rehabilitation of injured athletes. The

results showed that a goal-setting intervention fostered adherence and

self-efficacy. McCalley and Midden (2002) provided participants

with feedback to increase household energy conservation behaviour. They showed

that participants who had set goals for themselves eventually saved more energy.

Fear Communication

Fear

communication can be effective to motivate certain behaviours. For example, health

behaviours, such as using condoms, can be encouraged by graphic information about

sexually transmitted diseases (Sutton & Eiser, 1984). An interesting study

by Smith and Stutts (2003) compared the effects of a fear appeal showing

the cosmetic effects of smoking (unhealthy looking faces) with the

effects on one's health (cancer). They found that both fear-appeal conditions

effectively reduced smoking. It must be noted that fear communication is only

effective (and ethically justified) when it is accompanied by explicit

guidelines on how to avert the health threat.

Modelling

refers to learning through the observation of others. Watching others behave and

showing the consequences can teach people to perform a new behaviour (Bandura, 1986).

Modelling is useful for all kinds of skills, for example, coping with criticism,

cooking meals, and using condoms. In a meta-analysis, Taylor, Russ-Eft

and Chan (2005) examined the effects of different types of

modelling. Do people learn more when a skill is modeled positively (showing what

one should do), negatively (showing what one should not do) or in combination?

These psychologists concluded that skill development was greatest

when role models were mixed, that is, when they showed what one should

as well as what one should not do.

118 Applying

Social Psychology Enactive Learning

The most effective way of learning a skill is

to try to accomplish it yourself. This is called enactive learning. In interventions,

people can be stimulated to practise a certain skill and evaluate it. For

instance, to foster students' interest in science subjects like mathematics,

Luzzo and his colleagues (1999) exposed students to either a video presentation

of two university graduates discussing how their confidence in maths had

increased (so-called vicarious learning) or a maths task providing these

students with feedback on their maths skills (enactive learning). The

enactive learning condition proved more effective.

Social Comparison

Social comparison — information on how

others are doing — may affect one's mood and well-being (Buunk &

Gibbons, 2007; Festinger, 1954). For example, in the context of coping with

cancer, Bennenbroek et al. (2003) provided cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy

with social comparison information to increase the quality of their life. The

intervention consisted of a tape recording of fellow patients telling their

personal stories about either the treatment procedure, emotions

experienced during the treatment, or a tape about the way they tried to

cope with the situation. The latter tape especially reduced anxiety over

the treatment and improved patients' quality of life.

Implementation Intentions

Implementation intentions are intentions to

perform a particular action in a specified situation (Sheeran, Webb

& Gollwitzer, 2005). Sometimes people are asked to formulate their

implementation intentions. For a person who wants a low fat diet an

implementation intention could be: 'When I am at the supermarket I will

put the low-fat butter in the shopping trolley', or 'When I am at the party on

Friday night and somebody offers me cake, I will decline'. Asking

people about their implementation intentions may increase the occurrence of

desirable behaviours. Steadman and Quine (2004), for instance, showed that

asking participants to write down two lines about performing testicular

self-examination led to the desired action. Likewise, Sheeran and

Silverman (2003) compared three interventions to promote workplace health and

safety and found that asking people to write down their implementation

intentions was the most effective.

Reward and Punishment

In general, people repeat behaviours that are

followed by a positive experience (reward) while avoiding a negative

experience (punishment). In the smoking example, a reward may

take the form of a refund for the costs of a smoking cessation course from the health

insurance company, if people quit smoking for at least three months. In

contrast, the government may punish people for smoking by

increasing the price of cigarettes. Furthermore, people can learn to reward or

punish themselves. For example, people who succeed in refraining from smoking for a

week could treat themselves to a cinema visit. In general, there is much evidence

for the effects of punishment and rewards. Punishment of undesirable

behaviours (for example, high fines for drunk driving) works

The Help Phase 119

best when it is accompanied by rewards for desirable behaviours

(for example, praise for staying sober before driving) (Martin & Pear,

2003).

Feedback

Feedback on accomplishments is essential in behavioural change. People

losing weight want to know how

much weight they have lost. Without feedback people become uncertain and their motivation deteriorates

because they do not know whether they have made progress (Kluger & DeNisi, 1998). Brug and his colleagues

(1998) provided people with tailored computer feedback on their diet

(vegetables, fruit and fat intake) and on

dietary changes. Both feedback types appeared to improve dietary habits.

Likewise, Dijkstra (2005) showed that

a so-called fear appeal to smokers — a single sentence of individual feedback (It appears you are not aware

of the changing societal norms with regard to smoking') — was twice as

effective in reducing smoking as no feedback.

|

Box 5.2 Interview with Professor Gerjo Kok of the

University of

Maastricht (The Netherlands)

Maastricht (The Netherlands)

One of the oldest and most prominent application areas of social psychological theory is health. Professor Gerjo Kok is one of the leading scientists in this

field.

'In addition to research on the causes of unhealthy

behaviour, we have developed a process protocol,

called Intervention Mapping, that provides guidelines and

tools for the development of health promotion programmes. In certain ways

(Continued)

120

Applying Social Psychology

the protocol is like this

book. It helps social psychologists, health organizations and/or the

government to translate social psychological theory and research in actual health programme materials and

activities and develop health intervention programmes that are maximally effective. In general I see a great

future for applied social psychology. I believe that social psychology

will play a growing role in the solution

of societal and health problems. Especially with regard to the study of

unconscious processes (such as habits), the field of group dynamics, and the study of environmental determinants of behaviour

(such as social norms and social

control) I expect social psychologists to become (even) more active.'

Interested in Gerjo Kok's

research? Then read, for instance:

Dijkstra, A., De Vries, H., Kok, G. & Roijacker, J.

(1999). Self-evaluation and motivation

to change: Social cognitive constructs in smoking cessation. Psychology& Health, 14(4), 747-759.

Kok,

G., Schaalma, H.P., Ruiter, R.A.C., Brug, J. & van Empelen, P. (2004). Intervention mapping: A protocol for applying health

psychology theory to prevention programmes. Journal of Health Psychology, 9, 85-98.

|

The Strategy

Methods have to be

translated into a specific strategy. The strategy is the actual intervention

people will get exposed to. For example, using television as the channel and modelling as the method, the

strategy would specify the age and gender of the role model. In the case of flu

vaccinations for elderly people, the strategy might be a television spot ad in

which viewers watch an older woman, with good health, being interviewed in her doctor's waiting room, before

having her vaccination.

To come up with strategies, a global

intervention plan could be made specifying the methods, channels, target groups, and

variables to be changed as identified on the basis of the balance table. Here are some examples:

·

Modelling (method) on television (channel) to motivate women

with overweight children (target group) to monitor

their children's body weight (variable to be changed).

·

Giving feedback (method) through the internet (channel) about

the length of time youngsters (target group) engaged

in exercise during the past week to support an increase in their physical stamina (variable to be changed).

·

Offering arguments (method) to motivate quitting smoking (variable to be changed) in a self-help book (channel) for

smokers of all ages (target group).

·

Repetition (method) of the word 'action' in the text of a model (method) presented in a leaflet (channel), designed

to motivate obese people (target group) to

formulate implementation intentions with regard to

reserving a seat with extra space (variable to be changed) on international flights.

The Help Phase 121

Next, based on these global intervention

descriptions, the social psychologist could select

a strategy for intervention. This usually takes place in two phases, a

divergent and convergent phase. In

the divergent phase, the psychologist lists as many strategies as possible.

In the convergent phase, he or she critically evaluates these strategies.

The

Divergent Phase: Inventing Strategies There are various techniques to generate

interventions:

·

Direct intervention association. Ideas for strategies can be based on all kinds of

sources, such as what one has seen on television, what makes intuitive sense,

what has proven to be effective in the

literature or what people have experienced themselves.

·

Direct method approach. This approach consists of looking at strategies that have

been used in similar situations. For example, suppose that the global

intervention description is: 'Provide information

on the appropriate use of a new type of toothbrush on a label to prevent mouth

injury in patients with bad teeth.' A psychologist

might then inspect existing labels on toothbrushes. Also labels with regard to other devices that could injure

people could be used to generate ideas.

·

Debilitating strategies. This approach is to come up with strategies that have undesired effects

on the problem. In the case of the global intervention description: 'Modelling

on television to motivate women to monitor their children's weight', the model

should probably not be a retired millionaire

on his ranch. By generating ideas of what would probably have no or reverse effects, we can learn about what would

have an effect, about the relevant dimensions of an effective intervention and

about ways to operationalize the strategies.

·

Interviews. Interviewing

people from the target group could generate additional ideas for strategies.

With the global intervention description, 'Modelling on television to motivate

women to monitor their children's body

weight', a woman with young children might be interviewed about her

preference for role models that might inspire her. Here is an example of such

an interview:

'If there was to be an

intervention on television in which a person tried

to convince you that monitoring your children's body weight is important,

what kind of person would you trust most?'

'I think I would be persuaded most by someone with experience of

the problem. It should be a mother but knowing how things are manipulated on

television I would need to have proof that she really is a mother with experience.'

'Do you have any other ideas about the person and what

the person would say that would help you to accept the

message?'

'The mother should be a sensible person, with

some education. I think she should also be serious about the

topic; after all, it is about the health of your children.'

'What kind of person would you trust least?'

'When I got, one way or another, the

impression that they are indirectly

trying to sell a commercial product I would immediately stop watching.'

trying to sell a commercial product I would immediately stop watching.'

This kind of interview — asking for the

desired but also the undesired characteristics —can generate new perspectives and ideas about

strategies. From the above, we learn that people might feel they are being manipulated, which should of

course be avoided.

122 Applying Social Psychology

·

Insights

from theory. This approach consists of looking at relevant social

psychological theories. With regard to the

method of goal setting, for instance, the difficulty of the goal is crucial (Strecher, Seijts, Kok, Latham, Glasgow, DeVellis,

Meertens & Bulger, 1995). In general, goals stimulate performance

when they are difficult and offer a challenge but at the same time are within someone's reach. Losing two pounds in two

months might not motivate a person much, because the outcome is not very

attractive, but losing 20 pounds in two months might be unrealistic. Thus, in developing strategies, the

psychologist should look carefully at what the theory predicts.

·

Insights from research. This approach consists of looking at relevant social

psychological research. For example, research shows that people are less

defensive with regard to processing

threatening information (for example on cancer risks) when their self-esteem is

boosted (Sherman, Nelson & Steele, 2000). Therefore, in developing a

fear-appeal we might want to include a self-esteem boosting method, for example,

asking people to write an essay on the good

things they have done recently (Reed & Aspinwall, 1998). Such 'manipulations'

are described in the method sections of empirical articles and can

provide the social psychologist with creative

ideas for strategies.

The

Convergent phase: choosing the strategy

The divergent phase often results in a laundry list of strategies.

Therefore, a limited number of strategies need to be selected. The choice for a

particular strategy or set of strategies must have both a theoretical and empirical

basis. First the strategy should take into account the conditions underlying the

theory. For example, in the

case of modelling, the theory specifies that the actual model must be similar

or at least relevant to people in the target group (Bandura, 1986). Second, it

is preferable that the choice of strategy is based on

empirical evidence from either laboratory experiments or field studies.

Ideally, evidence ought to be available for the combination of the channel, the method, the strategy, the

variable to be changed and the

target group. For example, for the global

intervention description: 'Modelling on television to motivate women to monitor

their children's body weight', the strongest evidence would come from a field experiment

in which such an intervention was tested in a specified target group against a control condition.

Somewhat weaker evidence would come from

testing the intervention video in the laboratory. The stronger the

empirical evidence for the intervention, the higher the chances that the

intervention will indeed be effective.

Sometimes evidence for

the effectiveness of a certain strategy is simply not there. In that case, especially when the costs of an

intervention programme are high, we recommend that the effectiveness of a new

strategy should first be tested through research.

BUILDING THE

INTERVENTION PROGRAMME

The Help

Phase 123

graphic designer who is acquainted with the

technological possibilities, such as paper sizes, colour use,

lay-out, visual angles, and dynamic effects. Here are some rules of thumb

for preparing materials, based on our own experiences:

·

Be as

specific as possible. In the case of a leaflet, formulate the final arguments,

write the introduction, link the arguments, and choose the font size and type.

In the case of a video with the method of modelling, write the script and

include what should be said and done and what should

happen in the video.

Be as

specific as possible. In the case of a leaflet, formulate the final arguments,

write the introduction, link the arguments, and choose the font size and type.

In the case of a video with the method of modelling, write the script and

include what should be said and done and what should

happen in the video.

·

In the

case of an intervention with several channels (for example, billboards and

television spots) or sequential elements (for example,

group counselling sessions), all parts must be fine-tuned and a protocol must be written as well as with

planning the intervention.

In the

case of an intervention with several channels (for example, billboards and

television spots) or sequential elements (for example,

group counselling sessions), all parts must be fine-tuned and a protocol must be written as well as with

planning the intervention.

·

If professional artists are

involved, it should be clear how much influence they can have over the end-product. The communication with professional

artists should be highly interactive and several versions may

have to be designed by the artist in order to come up with a product.

·

The intervention often includes more than one

strategy. In principle, all aspects

of the intervention that can be read, seen or heard should be part of a

strategy. Thus, the colours, the sizes, the

sounds, the timing, the wording, the movement, the background, the aspects of

the background, and the specific

shapes should all refer to an identifiable strategy. One way to test

this is to point to a single aspect of the intervention and ask: What strategy

is this part of and what is the method of

operationalization?'

Pre-Testing the Intervention

Each planned intervention must be pre-tested. The

primary function is to improve the intervention and to avoid major flaws in the

design. A pre-test does not necessarily include a behavioural measure. It primarily

ensures that the target group will attend to the message as well as understand the

message. For example, to assess if people from the target group attend

to the persuasive message, they may be asked: 'Did you find the information

interesting?', 'Why did you find it not interesting?', and 'Were you still able to

concentrate on the message at the end?' In addition to such general questions, one

may add more specific questions. For example, when the social psychologist has

chosen a role model who is trying to persuade members of the target group,

there may be questions like 'How similar do you feel to the person

in the video?', 'How sympathetic do you find the person in the

video?', 'Did you believe the person on the video indeed

suffers from disease X, which he claims to do?', and 'What aspects of the model

should be changed for you to believe the person?'. The format of the

pre-test usually includes exposing a few target group members to the

preliminary intervention and assessing their reactions. This assessment

can be done in different ways.

· Interview. This

is in general a useful method to pre-test the intervention. One may have interviews

with individuals from the target group and ask questions like the ones above.

In addition, one may ask more specific questions.

For instance, people may be asked to read a leaflet and tell the interviewer

about their reactions, how reliable they found the information, how realistic

they

found it, and what they liked or did not like about the content or layout.

124 Applying Social Psychology

·

Quantitative assessment With

this type of pre-test, people from the target group answer closed questions about the intervention in a

questionnaire. For example, they may be asked to rate the reliability of the

source on a 7-point scale (from 'not at all reliable' (1) to 'very reliable' (7)) or they may be asked whether the intervention

'took too much time' , 'was just right' or 'was too short'. With a more

experimental paradigm, when one wants for example to use a sticker to indicate the location of the

fire-extinguisher in the building, this sticker could be pretested by comparing different versions.

·

Recall. The psychologist may also

use a recall task, which assesses which aspects of the intervention

people from the target group remember after having being exposed to the intervention.

This might give an insight into which strategies have the highest salience.

Imagine a billboard depicting a

celebrity promoting safe sex, but when individuals from the target group are

asked to recall the characteristics of the billboard, half of them only

remember the name of the celebrity and

not what he or she was promoting. In this case, the salience of the messenger has apparently distorted the message of

the intervention.

·

Observation: People from the target group may also be observed while

being exposed to the intervention. For example, in the case of

testing a billboard, eye movements may be monitored to track which aspects of the billboard they pay most attention.

Likewise, when testing an internet website, the link-choices and the time spent

on each page might be monitored.

·

Expert opinions For

pre-testing the intervention, one may also ask the experts involved in bringing about the effects of the intervention.

(For example, in the case of a leaflet to increase treatment adherence a

doctor might be asked to give his opinion.) Or a shop-keeper who is supposed to hand out a leaflet to everyone who

buys product X may be asked whether he or she thinks people will indeed look at

the leaflet.

In general, participants seldom agree

completely about an intervention in a pre-test. Therefore, an applied social psychologist must

not only look at the pre-test data, but must

also consider theoretical aspects as well as empirical evidence that may be relevant. After revisions have been made, the

improved intervention can be pretested

a second time. The final version of the intervention can now be developed and distributed.

IMPLEMENTATION OF THE INTERVENTION

When

the intervention has been developed the implementation process can start. The

implementation process has one major goal: to ascertain that the intervention

is used as intended. Thus, when a psychologist develops an

intervention campaign with leaflets and television advertisements, members of

the target group must be exposed to these messages. When all members are exposed to

the intervention (for example, they have all read the leaflet or have at least

seen one television advertisement), the intervention is

implemented optimally. Note that implementation is not about the effects of the

intervention but about positioning the intervention in such a

way that it can have its effects.

The core challenge of the implementation

phase is that the extent to which the target group is exposed to the

intervention depends on the people and organizations that are involved

in the distribution of the intervention. For example, with regard to a leaflet

The

Help Phase 125

Figure

5.3 Proportion of people who report needing the intervention programme, who

are aware of its existence, who have started using it and who have completed

the programme

about medicine intake, pharmacists may be

involved by motivating their employees to distribute the leaflet to all patients

getting a specific medicine. We cannot expect that all

these people are as motivated to get the target group members exposed to the

intervention as the initiators and developers of the

intervention. Therefore, the implementation of an intervention involves motivating others and removing

any perceived obstacles to allow them to

engage in their specific tasks.

Sometimes people who help

with the implementation are simply not aware of the intervention. Paulussen and his colleagues (1995; see also

Paulussen, Kok & Schaalma, 1994)

studied the implementation of an educational programme consisting of several lessons designed to promote AIDS

education in classrooms. Almost all the teachers had initially expressed an

interest in participating. Yet only 67 per cent of the teachers were aware of its existence on the

curriculum and only 52 per cent initially started to teach it. Although

Paulussen et al. (1995) did not assess whether the teachers finished a whole curriculum, this percentage

is likely to be substantially lower (see Figure 5.3).

Thus,

although psychologists may develop an excellent intervention programme, if only a

few people are actually exposed to the intervention because professionals who are

essential for its implementation, such as teachers or doctors, are not aware of

it or do not use it properly, the impact of the intervention

on the problem may be small or non-existent.

The

Implementation Process

126 Applying Social Psychology

dissemination

adoption

adoption

implementation

continuation

Figure

5.4 The diffusion process of innovations

large-scale changes in the use of an

innovation (for example, using a new toothbrush or using a new method to

quit smoking) take place in time. This process is referred to as the diffusion process. Rogers distinguishes four phases. We will

illustrate the process here with an example of a leaflet for battered women to

get professional help. This leaflet is to be handed out by general

practitioners if they suspect domestic violence.

1.

Dissemination phase. In this phase the general

practitioner becomes aware of the existence of

the leaflet on domestic violence and discusses it with colleagues.

2.

Adoption phase. In this phase the

practitioner becomes motivated to use the innovation and to hand out the leaflet to patients who are

suspected to be victims of domestic violence.

3.

Implementation

phase. In this phase the doctor actually engages

in the behaviour that will expose the target group to the intervention: he hands out

leaflets to the right patients.

4.

Continuation phase. In this phase handing out

the leaflet becomes normal practice.

In stimulating the diffusion process, all

four phases will have to be addressed: raising awareness among general practitioners,

motivating such practitioners to detect target group members (i.e., women who may be

victims of domestic violence), and to hand out the leaflet to these women, supporting the

practitioners in the actual execution of the behaviours, and providing feedback

and reinforcement to maintain the behaviours (for example, by calling

practitioners on the phone and giving them support and advice).

Note that the diffusion process highlights the phases in

the implementation process. It does not define all the parties that are

involved in the implementation, except for the end users of the innovation

(in the above example the general practitioners). The next step is to identify all the people

and organizations involved in the implementation process. For each of the four diffusion

phases, different people and organizations may be involved.

Mapping the

Implementation Route

The Help Phase 127

involved in the

implementation and their motivations and barriers to performing their task in the

implementation are mapped. Developing an implementation route consists of three steps:

1.

Mapping

the actors. The route shows the actors in the relevant networks in which they communicate and their means of communication. For

example, with regard to the implementation of: 'A leaflet with

information and arguments for battered women to get professional help',

individual general practitioners are members of a regional organization, which

is part of the national organization for

general practitioners. Within and between these levels of organization, individuals and organizations

communicate via different means, including for example, formal meetings,

professional journals and email. Furthermore, patients who read the leaflet

and decide to seek professional help should be able to make a first appointment

very quickly. Thus, the organizations

providing professional help to battered women must also be involved in

the implementation.

2.

Assessing the motivations and the barriers for actors. For a successful implementation, each of the actors will have to engage in a specific task. For

example, general practitioners should be

motivated to engage in detecting battered women and should dedicate some time

to this task. Furthermore, the board members of

a general practitioners' organization should be motivated

to invest some money in persuading general practitioners to perform the

detection or to persuade insurers that the detection

of battered women should be reimbursed. Thus the implementation

route contains for all actors a diagnosis of the potential problems to engaging

in the implementation's task and the specific barriers to performing it.

3.

Identifying relevant policies. Besides identifying the actors involved, the relevant

policies also need to be known. For example, it is possible

that there is a policy for general practitioners that says that the general

practitioner will not engage in detection tasks with regard to family matters. Although some general practitioners might

still be motivated, this would rot be an ideal situation for the implementation

of the intervention. Or it may be that there is a law that says that the police can only offer protection to a

battered woman when there is objective evidence

of domestic violence. This might inhibit women from seeking professional help.

This law would counter the desired effects of the intervention structurally.

The Implementation

Plan

When the actors,

organizations and policies have been identified and the motivation and the perceived

barriers to the actors have been mapped, the implementation plan can be

developed. The implementation plan consists of all the steps that should be

taken to stimulate the actors to conduct their task(s) in the implementation.

In developing

an implementation plan, the social psychologist must take two factors into account.

Implementation

Goals

For each actor or

level of actors and for each of the four diffusion phases, goals may he

formulated. For example, a goal for general practitioners in the first diffusion phase

could be: '80 per cent of the practitioners heard about the existence of the intervention

formulated. For example, a goal for general practitioners in the first diffusion phase

could be: '80 per cent of the practitioners heard about the existence of the intervention

128 Applying Social Psychology

material

on domestic violence and at least 50 per cent discussed the material with colleagues'.

On the organizational level, organizational goals should be formulated. For example,

a goal in the adoption phase could be: 'The board of the national organization for

general practitioners has decided to set aside one article in the professional

journal on domestic violence and to develop a pre-publication on it in their

communication with the regional organizations'. In principle, the goal

should be that every actor has a positive

attitude towards the implementation, or perceives their task in the implementation

as a legitimate part of their job.

Action Plans

Next,

the implementation plan specifies all the actions that must be taken to reach

the goals. This implementation manual specifies how

the goals can be reached. For example, the above goal with regard to

the awareness of general practitioners of the intervention

materials may be reached by actions directed at their national organization. For

example, we might want the board to be motivated enough to decide that some articles

on the detection of battered women should be published in their professional journal.

The Actual Implementation

The

actual implementation exists through executing the implementation plan. Thus, all

kinds of actions will have to be taken to inform and motivate the actors and to

take away

perceived or actual barriers for actors and to support the implementation. Actors may receive information designed to

motivate them, or permission to act from a higher level in their organization

or the means, in time or money, to do their part in the implementation. To support the execution of

the implementation tasks, the actors might

be contacted by e-mail, by letter, by telephone, by advertisements in professional journals, by presentations at meetings or

by their internal communication channels.

As may

be clear by now, the actual implementation of the intervention is time-consuming

and much work has to be done before any target group members will be exposed

to it.

The Evaluation

To

assess whether the problem that was targeted has indeed changed for the good, the

last step in this intervention-development cycle is to evaluate the effects of

the intervention. At least three types of evaluation are important: the effect evaluation, the process

evaluation and the cost-effectiveness

evaluation.

In the effect

evaluation, the extent to which variables that are directly related

to the problem have changed over time is assessed. At the very

least the effect of the intervention

The Help Phase 129

on the specified outcome variable in the process-model should be

assessed. There are, however, more outcome variables that may

be evaluated to determine the effectiveness of the intervention.

Imagine the case of the problem of obesity in which the level of

exercise is the variable that the social psychologist aims to influence. The

primary outcome variable in the process model is the level of

exercise. However, the number of people who engage in sufficient exercise

can also be a meaningful outcome variable. In addition, the

percentage of obese people six or 12 months after exposure to the intervention

could be an important outcome measure.

To

assess to what extent the effects are temporary or permanent, an appropriate follow-up

period must be specified. Long-term behavioural effects can be assessed 12

months after the exposure, although the 12 month period is based on consensus rather than on rationale.

The best follow-up periods are based on specific arguments for the behaviour that is targeted. For example, because in

smoking cessation most smokers who

relapse do so within the first six months after the initiation, a six

month follow-up should be sufficient; after this period very few ex-smokers

relapse.

In

the process evaluation, the

elements that are preconditions for the intervention to be

successful are assessed. There are two types of process evaluation. The primary-process evaluation refers

to an assessment of the changes in the variables that underlie the

changes in the outcome variables. For example, when the process model states

that prejudice towards Muslims is caused by media misrepresentations

of Muslims, the changes in prejudice as a result of unbiased publicity

might be assessed in a primary-process evaluation. In principle, all the

variables in the balance table that were targeted by

the intervention(s) are primary-process variables and may be evaluated. The secondary-process evaluation refers

to an assessment of the extent to which effective elements of the intervention

have indeed been executed. For example, for individual counselling

it may be essential that the counselor and the client develop a 'therapeutic

relationship' because the therapeutic relationship serves as one of the methods

of intervention. In a secondary outcome assessment, the extent to

which the therapeutic relationship has been formed is assessed.

In a cost-effectiveness evaluation the

costs of interventions are assessed and compared with the benefits.

For example, obesity has huge societal costs specifically in terms

of healthcare provision. If an intervention leads to a yearly decline of 500

people suffering from obesity, the healthcare savings can be

calculated. A second aspect of the cost-effectiveness concerns the costs of

intervention. The intervention development and implementation are

costly as they involve professional labour and material costs. For a television

advertisement to be broadcast, the costs for broadcasting must be paid. In the cost-effectiveness

evaluation the savings caused by the intervention are compared to the

costs of the intervention.

It

is important that for the effect evaluation as well as the cost-effectiveness

evaluation there are usually data sources available. Many

commercial research agencies gather information on societal phenomena.

such as the percentage of obese people and the number of unemployed. Thus, it may

not always be necessary to gather additional data. On the other hand, it is important that outcome

variables are carefully

130

Applying Social Psychology

Figure 5.5

Number of smokers (x 1000) 'as a function of type of channel' that were reached by the Millennium campaign 'I can do that too'

assessed.

Therefore, a self-developed outcome assessment may be necessary. Especially

with regard to the process evaluation, reliable measures must often be developed.

(For further reading on the evaluation of intervention we would refer to other

sources such as Action

evaluation of health programmes and changes by John Ovretveit,

2001.) In the last paragraphs of this chapter we present a case study of a large-scale

intervention that was successfully implemented to help smokers quit in the

Netherlands.

Case

Study: The Millennium Campaign 'I Can Do That Too'

In

the Netherlands, the Dutch Expertise Center of Tobacco Control developed the

Millennium campaign 'I can do that too' to reduce the percentage of smokers.

The campaign consisted of a series of interventions through

several channels to stimulate smokers to quit and support their attempt.

The campaign started in October 1999 and ended in February 2000.

The intervention programme is depicted in

Figure 5.5. In addition, the population was exposed to free publicity about the

campaign. In the written media, no less than 519 articles were published on the

Millennium campaign and 79 radio and TV items gave information on it.

The effectiveness of the campaign was

assessed using a so-called panel design with measurement control

groups (see Box 5.3). That is, before the campaign started, in October

1999 (Time 1), an initial measurement among smokers was conducted. This

The

Help Phase 131

group constituted the panel group. It is

common that such measurements may influence measurements done later

with the same group. If one finds a change in the panel group, this

could be an artefact of the first measurement (for instance, because it made

them aware of the risks of their smoking habits). Therefore, when the second

measurement was applied to the panel group (thus at Time 2, in

February 2000) there was also a control group of smokers with no Time 1

measurement. The same was done for the Time 3 measurement (January 2001).

1.

seven-days' abstinence (not smoking for at

least the past seven days);

2.

having engaged in an attempt to quit;

3.

having positive intentions to stop smoking.

It was found that, at Time 2, those smokers

who had watched the TV programme or the TV talk show at Time 1 had made

significantly more attempts to quit. The long-term follow-up

(Time 3) showed that smokers who knew the Millennium campaign also had more positive intentions

to stop smoking. The researchers concluded that the Millennium campaign led more smokers to quit smoking and, for those who

had not yet made an actual attempt,

it had made smoking cessation a higher priority.

132 Applying Social Psychology

Developing an intervention programme includes the following steps: Box 5.4 The Help Phase: Developing an Intervention Programme

1.

Make a list of all the

causal variables in the process model and determine for each of them how modifiable they are and how large their

effect will (probably) be. Make a balance table to summarize the results.

Choose those factors for your intervention that are modifiable and that have

the greatest effect on the outcome variable.

2.

For each of the selected variables, come up with a channel, a

method and a strategy to influence this

variable. Justify your choices for the channels and methods and report on the use of different skills

to look for appropriate strategies

(i.e., direct intervention association, direct method approach, explore debilitating strategies, conduct interviews, look

at relevant theories and research).

3.

Reduce the potential list of strategies. In

selecting suitable strategies take notice of the conditions underlying the theory

that the particular strategy is based on

and look for research that supports the effectiveness of that particular

strategy. Develop the strategies you have chosen into an holistic intervention programme.

4.

Pre-test the intervention

programme by means of interviews, quantitative assessments, recall tests

or observations.

5.

Develop an implementation

route. Map the actors involved in the intervention's

implementation, assess the actors' motivations and the barriers they perceive,

and identify relevant policies.

6.

Develop an implementation plan. What steps

have to be taken to mobilize and motivate the actors

involved in implementing the intervention?

7. Implement

the intervention programme and evaluate its effectiveness.

SUGGESTED FURTHER READING

Bartholomew, L.K., Parcel, GS., Kok, G &

Gottlieb, N.H. (2006). Planning health

promotion

programmes: An

intervention mapping approach. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Ovretveit, J.

(2001). Action evaluation of health programmes and changes: A handbook for

a

user-focused

approach. Abingdon, UK: Radcliffe Publishing.

Rochlen, A.B., McKelley, R.A. & Pituch, K.A. (2006). A

preliminary examination of the 'Real Men, Real Depression' campaign. Psychology

of Men & Masculinity, 7(1), 1-13.

Smith, K.H. & Stutts,

M.A. (2003). Effects of short-term cosmetic versus long-term health fear appeals in anti-smoking

advertisements on the smoking behaviour of adolescents. Journal of Consumer

Behaviour, 3(2), 157-177.

Van Assema, P.,

Steenbakkers, M., Stapel, H., Van Keulen, H., Rhonda, G & Brug, J. (2006). Evaluation of a Dutch public-private

partnership to promote healthier diet. American

Journal of Health Promotion, 20(5), 309-312.

The Help Phase 133

ASSIGNMENT

5

A

company that produces computer software asks you, as a social psychologist, for

advice. The company consists of 10 departments, each of 50 employees,

with every department managed by an executive. These 10 executives

are in turn subordinate to a team of five directors that leads the

company. Although 50 per cent of the employees are female, of the

directors and executives only one person — the executive that runs the household

department — is female. The team of directors asks you how they can improve

the upward mobility of women in the company's hierarchy so the company will

have more female leaders in the future.

(a)

Read the following two articles:

Ritter,

B.A. & Yoder, J.D. (2004). Gender differences in leader emergence persist

even for dominant women: An updated confirmation of role congruity theory.

even for dominant women: An updated confirmation of role congruity theory.

Psychology of

Women Quarterly, 28(3), 187-193.

Eagly, A.H. & Karau, S.J. (2002). Role congruity

theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychological

Review, 109(3), 573-598.

Select from these articles causal factors and

develop a process model. Make sure that you limit the number of variables to

about 10 and don't take more than four steps back in the model.

(b)

Estimate for each causal factor in the

process model its modifiability and effect size. Make a balance table

and select the causal factors at which the intervention should be targeted.

(c)

For each of the selected factors, come up

with possible strategies to influence this factor. Use direct

intervention association and the direct method approach, explore debilitating

strategies, conduct interviews, and look at relevant theories and research.

(d)

Reduce the potential list of strategies by

examining their theoretical and empirical basis.

(e)

Outline a global intervention plan, a number

of ways to present the intervention and make a plan for the implementation of

the intervention.

(f)

Develop an evaluation procedure to determine

the effectiveness of the intervention programme

Menerapkan Psikologi Sosial Dari Masalah dengan Solusi

Abraham P. Buunk dan Mark Van Vugt

Komentar

Posting Komentar