Community and Power

Nelson, G. & Prilleltensky, J (2005). Community Psychology In Pursuit

Of Liberation And Well-Being. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

p.93-114

5

Community and Power

Chapter Organization

We

would like you to think about the four following situations:

1.

A situation in which you experienced a sense of community through bonding,

close relationships and attachment.

2.

A time when you felt excluded and isolated.

3.

A situation in which you felt empowered to do something or achieve something.

4.

An occasion in which you felt powerless and without a sense of control.

Write down how you felt in each one of these

situations.

In

this chapter you will learn about community and power. The specific aims of the

chapter are to:

■ define and critique the concepts

■ study their value-base

■ identify their implications for the promotion of well-being and

liberation and for the perpetuation of oppression.

Have

you done the warm up exercise? How did you feel when you experienced a sense of

community? Did you feel supported, appreciated? Did you feel constrained?

What

about power? Did you feel good when you were in control of a situation? Did

power ever get to your head? Most people experience both sides of community and

power: positive aspects and negative aspects.

Positive

aspects of community include social support, cohesion and working together to

achieve common aims. Negative aspects of community include rigid norms,

conformity, exclusion, segregation and disrespect for diversity. Positive

aspects of power include the ability to achieve goals in life, a sense of

mastery and a feeling of control. Negative aspects of power include the

capacity to inflict damage or to perpetuate inequality. Our challenge as

community psychologists is to promote the growth-enhancing aspects of community

and power and to diminish their negative potential. We want to use community

and power io promote social justice and not to stifle creativity or perpetuate

the status quo.

Our

work is difficult because it is highly contextual. It's hard to make rules that

apply to all contexts. On one hand, we know intuitively that sharing happy and

sad moments with friends and others is beneficial for personal well-being. On

the other hand, groups can e %vertu!

norms of conformity that suppress the creativity individuality of their meml similarly,

we know that disempowered people conk use more htical power to advance eir

legitimate aims, hut that doesn't mean that more is always a good thing, neither for

disempowered nor for over-empowered people.-

• 4fisempowered does not make a person into a right-eous individ ese

potential scenano 4.. us that the outcomes of community and power

are highly contextual. We need to know the specific circumstances and dynamics

of community and power belOre we endorse either of them. Who will benefit from

a set of community norms? Who will gain and who will lose from giving a certain

group of people more power? What is the impact of community and power for

well-being and liberation? These are the key questions that we want to address

in this chapter.

Community and Power

Community

psychology (CP) has traditionally emphasized the role of community over power

in promoting well-being. The sense of community metaphor discussed in Chapter 2

dominated the field's narrative for its first decade or so. In a corrective

move, Rappaport (1981,1987) introduced the concept of empowerment to indicate

that power and control over community resources would be just as important as a

feeling of communion. As we will see in this chapter, the concept of

empowerment has li mitations of its own, but at the time it was introduced it

served an important fimction: it drew attention to power dynamics affecting

well-being. Feminist critics of empowerment like Stephanie Riger (1993) pointed

out some risks inherent in the concept. First, she reminded us of the danger of

swinging the pendulum too much towards individual power and forgetting the need

for sense of community. Second, she recognized that empowerment may become

another psychological variable that would lead to individual changes instead of

social changes. Riger's critique is reminiscent of Bakan's (1966) distinction

between agency and communion. Agency is the power to assert ourselves, whereas

communion is the need to belong to something larger than ourselves. The

conflict between these two complementary tendencies is played out in the field

of CP through the tension between empowerment and community.

In

this book, we wish to avoid dichotomies such as community or power. We wish to

push the CP agenda further and claim that psychological empowerment and

empowering processes are not enough without social justice and a redistribution

of resources (Speer, 2002). At the same time, achieving power without a sense

of community, within and across groups, may lead to untoward effects

(Nisbet,1953).

Without

empowerment we risk maintaining the status quo and without community we risk

treating people as objects. Let's explore this thesis and the ways in which

these two concepts complement each other.

What Are Community and Power?

Community

At

its most basic level, the word community implies a group or groups of citizens

who have something in rommot. We can think of a geographical community such as

your neighbourhood or country or we can think of a relational community such as

a group of friends or your religious congregation (Bess, Fietv-i, Sonn &

t3;11:01.1, 2002). Members of a relational group may share a culture or a corniTdon interrcr

There

are countless forces and dynamics that

bring people together. Some of us

feel quite close to the community

of community psychologists, while other

feel close to the fans of a sport team or to members religious grow- -'‘-'mt

-.;'

17

-1-zs

can feel close to these three groups at. the same tin:

-can

belong to multiple communi- ties

concurrently-Of meanings of the word 'community' we have chosen to

concentrate on two that are important to the work of community psychologists:

sense of community and social capital.

Sense of community. Seymour Sarason

(1974), one of the founders of the field of CP, identified sense of community

as central to the endeavour of the field.

In

his view, sense of community captured something very basic about being human:

our need for affiliation in times of sorrow, our need for sharing in times of

joy; and our need to be with people at all other times. He defined sense of community

as:

the

sense that one belongs in and is meaningfully a part of a larger collectivity;

the sense that although there may be conflict between the needs of the

individual and the collectivity, or among different groups in the collectivity,

these conflicts must be resolved in a way that does not destroy the

psychological sense of community; the sense that there is a network of and

structure of relationships that strengthens rather than dilutes feelings of

loneliness. (Sarason, 1988, p. 41 )

Since

Sarason's (1974) coinage of the term,

others have tried to

operationalize and distil the meaning of sense of community, all in an effort

to understand-the positive or

negative effects of this phenomenon.

McMillan and Chavis (1986) are credited with formulating an enduring

conceptualization of sense of community.

According

to them, the concept consists of four domains: (a) membership, (b) influence,

(c) integration and fulfillment of needs, and (d) shared emotional connection.

These

four domains of sense of community sparked a great deal of interest and

research in the field of CP. A special issue of the Journal of Community Psychology in 1996

(volume 4) and a recent book on the subject summarize very well progress in the

area (Fisher, Sonn & Bishop, 2002).

The

interest in communities is justified in a world where groups intersect and

experience conflict over resources. We live in a world where communities of

various identities share space, time, work, past, present and future. Each

community has to value its own diversity as well as the diversity present in

other groups.

What,

on the surface, may look similar may hide vast differences. Not all aboriginal

people share the same culture (Dudgeon, Mallard, Oxenham & Fielder, 2002),

nor do all immigrants experience the same challenges (see Chapter 17). We can

talk about a community of women, within which there are obviously multiple

communities of chicanes, aboriginal, African-American, privileged, poor,

disabled and able bodied women. Every time we invoke a group of people, there

are going to be multiple identities within it (Arellano & Ayala-Alcantar,

2002; Serrano-Garcia & Bond, 1994). Communities may define themselves in

exclusive terms reminiscent of apartheid or in inclusive terms reminiscent of

solidarity.

Social Capital. While sense of community attracted a lot of

attention within CP, allied terms such as 'community cohesion' and 'social

capital' gained currency in other disciplines such as sociology, community

development and political science.

We

find much in common between these two concepts and CP (Perkins, Hughey &

Speer, 2002). In essence, they speak about the potential of communities to

improve the well-being of their members through the synergy of associations,

mutual trust, sense of community and collective action (Kawachi, Kennedy &

Wilkinson, 1999; Veenstra, 2001). In short, they deal with the intersection of

people, well-being and community. The main difference between sense of

community and social capital lies in the level of analysis. Whereas sense of

community is typically measured and discussed at the group or neighborhoods

level, social capital research has looked at the results of cohesion at state and

national levels. Community psychologists Douglas Perkins and Adam Long (2002)

maintain that sense of community is only a part of social capital. They suggest

that social capital consists of four dimensions: (a) sense of community, (b) neighboring,

(c) collective efficacy and (d) citizen participation.

In

his widely popular book Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American

Community, Robert Putnam (2000) distinguished between physical, human and

social capital:

Whereas

physical capital refers to physical objects and human capital refers to

properties of individuals, social capital refers to connections among

individuals — social networks and the norms of reciprocity and trustworthiness

that arise from them. (p. 19)

In

our view, social capital refers to collective resources consisting of civic

participation, networks, norms of reciprocity and organizations that foster (a)

trust among citizens and (b) actions to improve the common good. Figure 5.1

shows the various dimensions of social capital identified by Stone and Hughes

(2002) in their study of social capital in Australian families. As may be seen,

social capital entails networks of trust and reciprocity that lead to positive

outcomes at multiple levels of analysis, including individual, family,

community, civic, political and economic well-being. Figure 5.1 summarizes the

types and characteristics of networks. Density, size and diversity are key

factors in the quality of community connections. Another important feature of

this figure is that the hypothesized outcomes influence the very determinants

of social capital. Some of the outcomes, such as civic participation, may

generate more social capital. Accordingly, we should see determinants and

outcomes of social capital as exerting reciprocal and not unidirectional

influence on each other.

Social

capital, in the form of connections of trust and participation in public

affairs, enhances community capacity to create structures of cohesion and

support that benefit the population and produce positive health, welfare,

educational and social outcomes. Vast research indicates that cohesive

communities and civic particI ipation in

public affairs enhance the well-being of the population. Communities with

higher participation in volunteer organizations, political parties, local and

professional associations fare much better in terms of health, education, crime

and well-being than communities with low rates of participation. This finding

has been replicated at different times across various states, provinces and

countries (Putnam, 2000; Schuller,2001; Stone & Hughes,2002; Wilkinson,

1996).

Measuring Social

The following are partial

sample items taken frorn the Social Capital Community Benchmark Study sponsored

by the Saguaro Seminar at Harvard University. The complete tool is available at

http://www.cfsv.org/ communitysurvey/docs/survey_instrument pdf.

5. This study is about

community, so we'd like to start by asking what gives you a sense of community

or a sense of belonging. I'm going to read a list. For each one say 'yes' if it

gives you a sense of community or a sense of belonging and 'no' if it does not.

Your old or new friends

The people in your

neighbourhood

Your place of worship

The people you work with or

go to school with

6. Generally speaking, would

you say that most people can be trusted or that you can't be too careful in

dealing with people?

16. Overall, how much impact

do you think people like you can have In making your community a better place

to live?

26. Which of the following

things have you done in the past twelve months;

Signed a petition?

Attended a political meeting

or ray?

Worked on a community

project?

Participated in any

demonstrations, protests, boycotts Of marches?

Donated blood?

33. I' m going to read a

list. Just answer 'yes' If you have been involved in the past 12 months with

this kind of group: •

An adult sports club or

league, or an outdoor activity club?

A youth organization like a

youth sports league, the scouts, 4-H clubs, and boys and girls clubs?

A parents' association, like

the PTA or PTO, or other school support or service clubs?

A neighborhood association,

like a block association?

A labor union?

A support group Of

self-help program?

34. Did any of the groups

that you are involved with take any local action for social or political reform

in the past 12 months?

Power

Since

the 1980s, community psychologists have discussed empowerment more often than

power per se (Speer,2002; Zimmerman,2000). For that reason, we begin with a

brief review of the former.

Empowerment. Empowerment refers to both processes and

outcomes occurring at various levels of analyses (Prilleltensky, 1994a;

Zimmerman, 2000). Empowerment is about obtaining, producing or enabling power.

This can happen at the individual, group or community and social levels.

Rappaport claimed that empowerment is 'a process: the mechanism by which

people, organizations, and communities gain mastery over their lives' (1981, p.

3); whereas the Cornell Empowerment

Group

defined it as 'an intentional ongoing process centered in the local community,

involving mutual respect, critical reflection, caring, and group participation,

through which people lacking an equal share of valued resources gain greater

access to and control over those resources' (1989, p. 2). The latter definition

starts talking about the process but ends with an emphasis on outcomes: control

over resources. We agree with Speer (2002) that a balance must be reached

between research and action on empowering processes and empowered outcomes.

Otherwise, we risk sacrificing one for the other. Not only are the two

components equally important, but they are mutually reinforcing as well. Based

on the work of Zimmerman (2000) and Speer and colleagues (Speer & Hughey,

1995; Speer, Hughey, Gensheimer & Adams-Leavitt,1995), we represent in

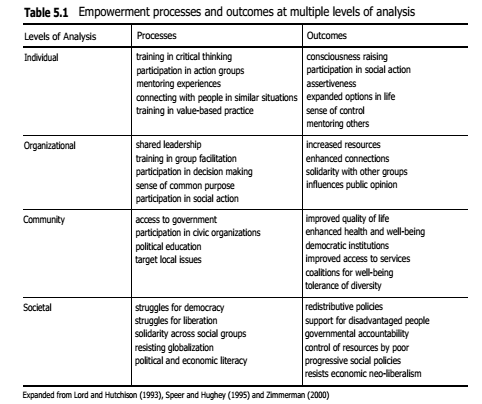

Table 5.1 the various domains

Table 5.1 Empowerment processes and outcomes at

multiple levels of analysis

Levels of Analysis Processes Outcomes

Individual

training in critical thinking

participation in action groups

mentoring experiences

connecting with people in similar situations

training in value-based practice

consciousness raising

participation in social action

assertiveness

expanded options in life

sense of control

mentoring others

Organizational

shared leadership

training in group facilitation

participation in decision making

sense of common purpose

participation in social action

increased resources

enhanced connections

solidarity with other groups

influences public opinion

Community

access to government

participation in civic organizations

political education

target local issues

improved quality of life

enhanced health and well-being

democratic institutions

improved access to services

coalitions for well-being

tolerance of diversity

Societal

struggles for democracy

struggles for liberation

solidarity across social groups

resisting globalization

political and economic literacy

redistributive policies

support for disadvantaged people

governmental accountability

control of resources by poor

progressive social policies

resists economic neo-liberalism

Expanded

from Lord and Hutchison (1993), Speer and Hughey (1995) and Zimmerman (2000)

and dynamics of empowerment at four levels of analysis. Similar to Figure 5.1

on social capital, some of the outcomes are reinforcing of the processes.

Better empowerment outcomes should generate more empowerment processes and vice

versa.

The

concept of empowerment stimulated much discussion in CP, with two special

issues of the American Journal of Community Psychology dedicated to it in 1994

(Serrano-Garcia & Bond, 1994) and 1995 (Perkins & Zimmerman, 1995).

Yet,

despite much progress in the field, some key issues remain underexplored. In

our view, these issues pertain to the multifaceted and dynamic nature of power.

Empowerment

is not a stable or global state of affairs. Some people feel empowered in some

settings but not in others, whereas some people work to empower one group while

oppressing others along the way. A more refined concept of power is needed to

understand better the concept of empowerment and its nuances.

From Empowerment to Power. Power is everywhere; it's in interpersonal

relationships, families, organizations, corporations, neighbourhoods, sports

and countries. Power can be used for ethical or unethical purposes. It can

promote well-being but it can also perpetuate suffering.

A

more dynamic conceptualization of power is needed, one that takes into account

the multifaceted nature of identities and the changing nature of social

settings. Moreover, we need a definition of power that takes into account

subjective and objective forces influencing our actions as community

psychologists.

In

the light of the need for a comprehensive conceptualization of power, we offer

a few parameters for clarification of the concept. Based on previous work, we

present them as a series of ten complementary postulates (Prilleltensky, in

press).

1.

Power refers to the capacity and opportunity to fulfil or obstruct personal,

relational or collective needs.

2.

Power has psychological and political sources, manifestations and consequences.

3.

We can distinguish between power to strive for well-being, power to oppress and

power to resist oppression and strive for liberation.

4.

Power can be overt or covert, subtle or blatant, hidden or exposed.

5.

The exercise of power can apply to self, others and collectives.

6.

Power affords people multiple identities as individuals seeking well-being,

engaging in ppression or resisting domination.

7.

Whereas people may be oppressed in one context, at a particular time and place,

they may act as oppressors at another time and place.

8.

Because of structural factors such as social class, gender, ability and race,

people may enjoy differential levels of power.

9.

Degrees of power are also affected by personal and social constructs such as

beauty, intelligence and assertiveness; constructs that enjoy variable status

within different cultures.

10.The

exercise of power can reflect varying degrees of awareness with respect to the

impact of one's actions.

We

expand here on the first and main postulate of our conceptualization of power.

We claim that power is a combination of ability and opportunity to influence a

course of events. This definition merges elements of agency or

self-determination on the one hand, with structure or external determinants on

the other. Agency refers to ability whereas structure refers to opportunity.

The exercise of power is based on the juxtaposition of wishing to change

something and having the opportunity, afforded by social and historical

circumstances, to do so. Ultimately, the outcome of power is based on the

constant interaction and reciprocal determinism of agency and contextual

dynamics (Bourdieu, 1990; Martin & Sugarman, 1999, 2000).

People

who are born into privilege may be afforded educational and employment

opportunities that people on the other side of town could never dream of.

Privilege can lead to a good education, to better job prospects and to life

satisfaction. These, in turn, can increase self-confidence and personal

empowerment. Lack of structural opportunities, such as the absence of good

schools or economic resources, undermines children's capacities for the

development of talents, control and personal empowerment (Bourdieu &

Passeron, 1977; Prilleltensky, Laurendeau, et al., 2001).

Another

defining feature of power is its evasive nature. You can't always tell it's

there. Nor can you tell how it's operating. Power is not tantamount to

coercion, for it can operate in very subtle and concealed ways (Bourdieu, 1986,

1990; Foucault, 1979a). According to social critics such as Bourdieu, Foucault

and Rose, people come to regulate themselves through the internalization of

cultural prescriptions. Hence, what may seem on the surface to be freedom may

be questioned as a form of acquiescence whereby citizens restrict their life

choices to coincide with a narrow range of socially sanctioned options? In his book

Powers of Freedom, Rose (1999) claimed that:

Disciplinary

techniques and moralizing injunctions as to health, hygiene and civility are no

longer required; the project of responsible citizenship has been fused with

individuals' projects for themselves. What began as a social norm here ends as

a personal desire.

Individuals

act upon themselves and their families in terms of the languages, values and

techniques made available to them by professions, disseminated through the

apparatuses of the mass media or sought out by the troubled through the market.

Thus, in a very significant sense, it has become possible to govern without

governing society— to govern through the

`responsibilized' and 'educated' anxieties and aspirations of individuals and

their families. (p. 88) (original emphasis)

The

point is that if governments or rulers want to exert power over their dominion,

they don't have to police people because people police themselves through the

internalization of norms and regulations (Chomsky, 2002). The problem with this

is that many groups absorb rules and regulations that are not necessarily in

their best interests, as can be seen in

Box 5.2.

The Power to Delude Ourselves?

In

April 2002, I, Isaac, travelled to California to teach a course at Pacifica

Graduate Institute in Carpinteria. I took a shuttle from the LA Airport to

Carpinteria. The driver, a congenial young man, started talking with passengers

about the economy, the cost of living in California, housing and traffic. He

shared with us that he had a BA in chemistry and that he worked full time In a

laboratory. In order to afford the cost of living in California, he also drove

a shuttle bus from the Los Angeles Airport several times a week, on weekends

and after work. He had two demanding jobs. While talking about the economy tie

said that he is 41 favour of a flat tax, because 'the rich should not be

punished for being rich'. I thought to myself, here is this guy who is working

probably 80 or more hours a week arid cannot

afford

the cost of living In California, and he is favouring a most regressive tax

system that benefits the rich arid disadvantages people like him because there

are fewer public resources, little public housing, arid poor social services. I

then arrived at the hotel and went to the gym.

As

I was cycling or the exercise bike I ferried on the TV which was tuned in to

the Suzie Orman show. Suzie gives financial advice over the phone. One of her

stock phrases was that your net worth was a reflection of your self-worth. She

told people that if they did not achieve financial wealth It was because they

did not think they deserved it! Here I was, a community psychologist trained in

thinking that people's problems have to do with contexts arid circumstances

arid opportunities In life, and in less than 30 minutes I encountered two

cultural discourses completely undermining my message. Is culture so powerful

that it can delude people into thinking that if they have problems it's their

own fault? Was the driver - deluding hirriself? What type of social power was

at play in the case of the driver and in the case of Suzie Orman?

Power,

then, emanates from the confluence of

personal motives and cultural injunctions. But, as we have seen, personal

motives are embedded in the very cultural injunctions with which they interact.

Hence, it is not just a matter of people acting on the environment, but of

individuals coming into contact with external forces that, to some extent, they

have already internalized. The implication is that we cannot just take at face

value that individual actions evolve from innate desires.

Desires

are embedded in norms and regulations (Bourdieu, 1990; Bourdieu & Passeron,

1977). This is not to adopt a socially deterministic position however; for even

though a person's experience is greatly shaped by the prescriptions of the day,

agency and personal power are not completely erased (Bourdieu, 1998; Martin

& Sugarman, 2000).

Think,

for example, about eating disorders. It is pretty clear that this psychological

problem cannot be dissociated from a culture that exalts thinness. Whereas many

women may wish to lose weight for health reasons, many others pursue thinness

because it is culturally and socially prescribed. We cannot simply say that

women have the power to lose weight or be healthy if they want to. We cannot

claim that they have the power to decide what is good for them, for that would

be a simplification. When many of us internalize norms that may be

counterproductive to our own well-being, this process restricts our choices.

Seemingly, we can do whatever we want. We can exercise or we can binge and

vomit, but our choices are highly circumscribed by norms of conformity we have

made our own, not necessarily because they are good for us, but because we are

subjected to social influences all the time. Instead of rebelling against

societal practices that feed us junk food and junk images, we censor ourselves.

No need for physical chains, many of us wear psychological chains.

Why Are Community and Power So Important?

Community

Sense

of community, social support and social capital can produce beneficial results

at the individual, communal and societal levels. Different kinds of social

support may be given and received. Instrumental support refers to the provision

of resources, such as lending money, helping a neighbour with babysitting or

sharing notes with a student who couldn't make a class. These are concrete

actions that people take to help each other. Emotional support, in turn, refers

to the act of listening and showing empathy towards others. When a friend

shares a problem with you, you show emotional support by being there, listening

non-judgementally and making yourself available. Bonding, sharing and building

relationships through common experiences can activate either type of support.

Social

support can increase or restore health and well-being in two ways (Cohen &

Wills, 1985). First, social support can enhance well-being through bonding,

affirming experiences, sharing of special moments, attachment and contributions

to one's self-esteem. The more support I have the better I feel and the more

likely I am to develop well-being and resilience in the face of adversity

(Prilleltensky, Laurendeau, et al., 2001). There is an accumulated positive

effect of having had good interpersonal experiences. According to our model of

well-being, relational wellbeing leads to personal well-being. The second

mechanism through which social support enhances well-being is by providing

emotional and instrumental support in ti mes of crises. As we noted in the

previous chapter, the stressful reactions associated with divorce, moves,

transitions or death may be buffered by the protective influences of helpful,

supportive relatives and friends.

Cohen

and Wills (1985) posited the buffering hypothesis to indicate that social

support may serve to enhance coping and to mitigate the negative effects of

stress.

In

their view, social support may prevent the perception of events as stressful

because people have sufficient instrumental and/or emotional resources to cope

with untoward situations. A person with sufficient supports may not experience

a situation as stressful, whereas others, without supports, may perceive the

situation as very threatening. A father who suddenly becomes unemployed but who

has a partner with a stable job and parents with economic resources may not

experience the loss of a job as does a father with no parents, no back-ups and

several kids to feed. The very phenomenon of unemployment is experienced

differently by the two men.

But

social support can buffer the effects of stress even when situations are

perceived as stressful. In the case of the man with supports, he will not worry

as much about his children because others will come through. In the second

case, the father has good grounds to worry about feeding his family. In effect,

Cohen and Wills (1985) postulate that supports can help in reducing the very

perception of a threat and in increasing the act of coping with the threat.

Various

channels lead to the positive effects of social support (Barrera, 2000). We can

think of agents and recipients of support, where the former is the one

providing the help and the latter is the one benefiting from it. Relational

well-being is characterized by relationships in which people assume the dual

roles of agents and recipients. Support may be given and received from a single

agent to a single recipient (friends talking to each other), from a single

agent to multiple recipients (grandmother helping her daughter and

grandchildren with shopping and cooking), from multiple agents to a single

recipient (a self-help group where various participants encourage and support a

person going through a hard time) and from multiple agents to multiple

recipients (a group of women raising funds and lobbying the government to help

refugee women). In some cases, the recipients are single individuals, whereas

in others they are small or large groups. Let's explore the significance of

social support for the various recipients.

At

the individual level, compared with people with lower supports, those who enjoy

more support from relatives or friends live longer, recover faster from

illnesses, report better health and well-being and cope better with adversities

(Cohen et al., 2000; Ornish, 1997). At the group level, studies have shown that

women with metastatic breast cancer have better chances of survival if they

participate in support groups. After a follow up of 48 months, Spiegel and

colleagues (1989) found that all the women in the control group had died,

whereas a third of those who received group support were still alive. The average

survival for the women in the support group was 36 months, compared to 19

months in the control group. Richardson and colleagues made similar claims of a

sample of patients with hematologic malignancies. They claimed that 'the use of

special educational and supportive programs designed to improve patient

compliance are associated with significant prolongation of patient survival'

(Richardson, Sheldon, Krailo & Levine, 1990, p. 356). Finally, Fawzy and

colleagues (Fawzy et al., 1993) found that patients with malignant melanoma

were more likely to die or experience recurrence of the disease if they did not

receive the group intervention that the experimental group received. Out of 34

patients in each group, of those who received group support, only 7 had experienced

recurrence and 3 had died at the five-year follow-up, compared with 13 and 10,

respectively, in the control group. Altogether, these three teams of

researchers found that social support can enhance health and longevity in the

face of deadly diseases.

In

the psychological realm, self-help groups provide support for people

experiencing addictions, psychiatric conditions, weight problems and

bereavement. In addition, support groups are also available for relatives and

friends caring for others with physical or emotional problems. Estimates of

participation in self-help groups in the United States range from 7.5 million

in 1992 to 10 million in 1999 (Levy, 2000). Moreover, self-help/mutual aid

groups can be found in many countries throughout the world (Lavoie, Borkman

& Gidron, 1994a, 1994b).

Keith

Humphreys is one of the leading researchers in the field of self-help groups.

In a study of people with substance abuse problems, Humphreys and colleagues

found positive results for African-American participants attending Narcotics

Anonymous and Alcoholics Anonymous. The sample of 253 participants showed

significant improvements in employment, alcohol and drug use, legal

complications and psychological and family well-being (Humphreys, Mavis &

Stoffelmayr, 1994). In another study Humphreys and Moos (1996) compared the

outcomes of self-help groups versus professional help on people who abused

alcohol. The outcomes were positive for both groups, but the cost of the

self-help option was considerably lower. As in these two examples, there is a

vast amount of research documenting the positive effects of self-help groups.

The research provides evidence that lay people can be very helpful to each

other, even in the absence of professionals leading the groups.

The

helper—therapy principle, according to which the provider of help benefits from

assisting others, has been documented in a variety of groups and settings.

Roberts,

Salem et al., (1999) showed that providing help to others predicted

improvements in psychosocial adjustment of people with serious mental illness.

Kingree

and Thompson (2000), in turn, demonstrated that mutual help groups helped adult

children of alcoholics to reduce depression and substance abuse.

Kingree

(2000) also found a positive correlation between levels of participation in the

group and increases in self-esteem. Borkman (1999) theorizes that members of

mutual help groups nurture each other through circles of sharing. Members

normalize each other's experiences and provide non-stigmatizing meaning to

their struggles in life. These hypotheses have been confirmed by, among others,

the case of GROW, a self-help group for people with psychiatric disabilities

that originated in Australia (Yip, 2002 ).

But

the benefits of participating in mutual help groups extend beyond the

participants themselves. Caregivers who attend these groups are better able to

assist family members and others in need of help. Positive effects were

reflected on children and elderly family members who require the attention of

the middle generation (Gottlieb, 2000; O'Connor, 2002; Tebes & Irish,

2000). Children whose parents participated in mutual help groups, for example,

exhibited fewer depressive symptoms and better social functioning than children

whose parents did not attend such groups. The results were sustained at the

six-month follow up (Tebes & Irish, 2000).

At

the community level, the research demonstrates that communities with high

levels of social cohesion experience better health, safety, well-being,

education and welfare than societies with low levels of cohesion. Based on US

research, Figure 5.2 shows the positive effects of social capital on a number

of well-being indicators. Putnam created a measure of social capital based on

'the degree to which a given state is either high or low in the number of

meetings citizens go to, the level of social trust its citizens have, the

degree to which they spend time visiting one another at home, the frequency

with which they vote, the frequency with which they do volunteering and so on'

(Putnam,2001, p. 48). He then compared how states with different levels of

social capital fare on a number of indicators. Putnam compared states on

measures of educational performance, child welfare, TV watching, violent crime,

health, tax evasion, tolerance for equality, civic equality and economic

equality. The trends in Figure 5.2 are representative of the results overall.

States with high levels of social capital and social cohesion enjoy better

rates of health, safety, welfare, education and tolerance. As can be seen in

the graph, there is a clear gradient: the higher the level of social capital,

the better the outcomes.

Figure 5.2

The effects of social capital in different states of the USA

Of

particular interest to us is whether social capital and social cohesion can

increase health and well-being. There is evidence to support this claim. In a

survey of 167,259 people in 39 US states, Kawachi and Kennedy (1999) lent

strong support to Putnam's claim that social capital reinforces the health of

the population.

Convincing

evidence making the link between social cohesion and health is also presented

by Berkman (1995), Kawachi et al. (1999), Veenstra (2001) and Wilkinson (1996).

Whereas the previous sets of studies investigated the effects of social support

on individuals, researchers like Putnam, Berkman, Kawachi and Wilkinson

assessed the aggregated effect of social cohesion on entire populations,

demonstrating that a sense of community and cohesion can lead to population

health.

Recent

research in economics demonstrates that fluctuations in gross domestic product

(GDP), inflation, unemployment and unemployment benefit levels influence the

overall well-being of entire countries. Using data from hundreds of thousands

of Europeans from twelve different countries, researchers found that when

unemployment and inflation go up, well-being goes down, and when unemployment

benefits and GDP go up, so does well-being (DiTella, MacCulloch & Oswald,

2001). In Switzerland, Frey and Stutzer (2002) found that levels of well-being

are not affected only by economic measures, but also by democratic

participation in referenda. Cantons with higher degrees of referenda and

citizen participation report higher degrees of happiness than those with lesser

citizen involvement. Taken together, the European research shows that

circumstances do matter. Indeed, the average level of subjective well-being is

affected by economic and political conditions and not only for those in extreme

conditions, for the studies showed effects for the population as a whole.

In

a recent and comprehensive review of the literature, Shinn and Toohey (2003)

catalogued the effects of community characteristics on their members.

Neighbourhoods with high socioeconomic status (SES) are predictive of academic

achievement, whereas communities low in SES and high in residential instability

are predictive of negative behavioural and emotional outcomes such as conduct

disorders and substance abuse. In these poor neighbourhoods, residents also

tend to have poor health outcomes, as measured by cardiovascular disease, poor

birth weight and premature births. Not surprisingly, exposure to violence tends

to be associated with poorer mental-health outcomes, depression, stress and

externalizing disorders.

In

addition to these correlational studies, Shinn and Toohey report the outcomes

of a longitudinal experimental study called 'Moving to Opportunity'. In this

study, families living in poor communities in Chicago were given the

opportunity to move to other parts of the city or to more affluent suburbs. Children

who moved to the suburbs did much better than those who moved within the city,

on a number of outcomes. Compared with children who moved within the city,

children who moved to the suburbs were much more likely to graduate from high

school (86% vs 33%), attend college (54% vs 21%), attend 4-year

university/college (27% vs 4%), be employed if not in school (75% vs 41%) and

receive higher salaries and benefits. In a similar project in Boston, children

who moved to more affluent parts of the city experienced dramatic decreases in

the prevalence of injury and asthma (74% and 65%, respectively) compared with

controls. In New York, behavior problems for boys who moved to low-poverty

areas were reduced by 30-43% relative to controls.

It

is interesting to note that people adapt to contextual conditions in order to

enhance the resiliency of their children. In low-risk neighbourhoods, low level

of parental restrictive control was associated with high academic achievements,

whereas in high-risk conditions, high level of parental control predicted

academic success.

High-risk

situations require high levels of parental intervention for optimal outcomes

(Shinn & Toohey, 2003). This finding shows that individuals are not mere

victims of adverse conditions, but many of them adjust and adapt their behavior

to the context of their lives.

Power

People

can use power to promote social cohesion or social fragmentation. But power

does not inhabit humans alone. Power is vested in institutions such as the

church, business corporations, schools and governments (Bourdieu &

Passeron, 1977).

Power

is important because it is central to the promotion or prevention of the goals

of CP: well-being and liberation. Without it, the disempowered cannot demand

their human rights. With too much of it, the over-empowered are not going to

relinquish privilege. With just about enough of it, it is possible that people

may satisfy their own needs and share power with others in a synergic form

(Craig & Craig, 1979).

Power to Promote Well-being. Well-being is achieved by the simultaneous,

balanced and contextually sensitive satisfaction of personal, relational and

collective needs. In the absence of capacity and opportunity — central features

of power —individuals cannot strive to meet their own needs and the needs of

others.

Personal

and collective needs represent two faces of well-being (Keating & Hertzman,

1999a; Marmot & Wilkinson, 1999). The third side of well-being concerns

relational needs. Individual and group agendas are often in conflict. Power and

conflict are intrinsic parts of relationships. To achieve well-being, then, we

have to attend to relationality. Two sets of needs are primordial in pursuing

healthy relationships between individuals and groups: respect for diversity and

collaboration and democratic participation. Respect for diversity ensures that

people's unique identities are affirmed by others, while democratic

participation enables community members to have a say in decisions affecting

their lives (Prilleltensky & Nelson, 1997). Without power to exercise

democratic rights, the chances of promoting the three dimensions of well-being

are diminished.

Power to Oppress. Power can be used for ethical or unethical

purposes. This is not just a risk of power, but part of its very essence. For

French social scientist Pierre Bourdieu, social capital is power. It is power

because it encompasses networks and resources available to serve personal and

class interests (Bourdieu,1986, 1990; Bourdieu & Passeron, 1977). Unlike

authors such as Putnam who tend to emphasize the positive in social capital,

Bourdieu is concerned with some of its negative effects. Like Bourdieu, we are

concerned with the possibility of social capital and power being used to

oppress others.

Oppression

can be regarded as a state or

process (Prilleltensky & Gonick,

1996).

With

respect to the former, oppression is described as a state of domination where

the oppressed suffer the consequences of deprivation, exclusion,

discrimination, exploitation, control of culture and sometimes even violence

(for example, Bartky, 1990; Moane, 1999; Mullaly, 2002; Sidanius, 1993). A

useful definition of oppression as process is given by Mar'i (1988):

'Oppression involves institutionalized, collective and individual modes of behavior

through which one group attempts to dominate and control another in order to

secure political, economic and/or socialpsychological advantage' (p. 6).

Another

important distinction in the definition of oppression concerns its political

and psychological dimensions. We cannot

speak of one without the other (Bulhan, 1985; Moane, 1999; Walkerdine, 1996,

1997). Psychological and political oppressions co-exist and are mutually

determined. Following Prilleltensky and Gonick (1996), we integrate here the

elements of state and process, with the

psychological and political dimensions of oppression. Oppression entails a state of asymmetric

power relations characterized by domination, subordination and resistance,

where the dominating persons or groups exercise their power by the process of

restricting access to material resources and imparting in the subordinated

persons or groups self-deprecating views about themselves. It is only when the

latter can attain a certain degree of conscientization that resistance can

begin (Bartky, 1990; Fanon, 1963;

Freire, 1972; Memzni, 1968).

The

dynamics of oppression are internal as well as external. External or political

forces deprive individuals or groups of the benefit of personal (for example,

selfdetermination), collective (for example, distributive justice) and

relational (for example, democratic participation) well-being. Often, these

restrictions are internalized and operate at a psychological level as well,

where the person acts as his or her personal censor (Moane,1999; Mullaly,2002;

Prilleltensky & Gonick,1996). Some

political mechanisms of oppression and repression include actual or potential

use of force, restricted life opportunities, degradation of indigenous culture,

economic sanctions and inability to challenge authority. Psychological dynamics

of oppression entail surplus powerlessness, belief in a just world, learned

helplessness, conformity, obedience to authority, fear, verbal and emotional

abuse (for reviews see Moane, 1999; Mullaly, 2002; Prilleltensky, 2003b;

Prilleltensky & Gonick, 1996).

What Is the Value-base of Community and

Power?

We

have already established the complementarily of values for personal, relational

and collective well-being in Chapter 3.

In a similar vein, Newbrough (1992a,1995) has argued that CP should try

to reach an equilibrium among the principal values of the French Revolution:

liberty, equality and fraternity. In our view, however, the desired equilibrium

has not been reached because the field has paid more attention to fraternity

than to the other two values. Unlike the value of solidarity, which has been

enacted through the concept of community, the values of liberty and equality

have not found similar expression in concepts such as power and justice

(Prilleltensky & Nelson, 1997). To achieve personal liberty and collective

equality, which are closely intertwined, we sometimes need to resort to

conflict. If collaborative means failure to produce a more equal distribution

of resources, then conflict may be necessary. The absence of conflict rewards

those who benefit from the current state of affairs, for the status quo is to

their advantage. Hence, for as long as they produce the desired results, we

would prefer conflict-free and fraternal means of promoting well-being. But if

they don't, we have to consider more assertive means (Hughey & Speer,

2002). We could try to persuade companies to provide better conditions for

their workers or we could create support groups for workers experiencing

stress. Furthermore, we could negotiate with factory owners to put in place

better working conditions such as ventilation, proper lighting and more breaks.

But if the owners deny all requests, workers may consider a strike or more

confrontational means of action.

The

erosion of social cohesion since the 1960s, at least in the US, has been amply

documented by Putnam (2000). This is a reminder that it is not enough to

reflect on the virtues of community structures; somebody has to support them!

In the age of economic neoliberal’s and globalization, governments are under

great pressure to reduce community and social services either to cope with

lower taxes or to reduce them. This has been the trend since the 1980s. As a

result, we see less investment in communities and more tax cuts that benefit the

rich (Gershman & Irwin, 2000; Sen, 1999b). In the light of these

developments, now more than ever we need social movements to fight for the

restoration of community services and for social investments (Bourdieu, 1998;

Kim et al.,2000).

How Can

Community and Power Be Promoted Simultaneously?

The

literature is quite abundant in examples that promote either a sense of

community (for example, Fisher, Sonn, & Bishop, 2002) or empowerment (for

example Perkins & Zimmerman, 1995;

Serrano-Garcia & Bond,1994), but not so vast in cases that promote both

simultaneously. Based on their research with community mental health groups,

Nelson, Lord and Ochocka (2001b) proposed the empowerment-community integration

paradigm. With input from various stakeholder groups they identified values,

elements and ideal indicators for the promotion of the new paradigm. The key

values for this paradigm are psychiatric consumer/survivor empowerment,

community integration and holistic health care and access to resources. The

principles, which correspond respectively to liberty, fraternity and equality,

seek an integration of empowerment and community interventions. (See we bsite.)

As

found by Nelson and colleagues, the three values are needed for the well-being

of psychiatric consumer/survivors. In our view, this integration is really

imperative for the promotion of individual, group, community and societal

well-being (see also Table 5.1). Social support by itself promotes a sense of

community but it does not rectify power imbalances, whereas combative social

action addresses power inequalities but doesn't necessarily promote cohesion.

Power

and community may be invoked to promote well-being, engage in oppression or,

finally, strive for liberation. Liberation refers to the process of resisting

oppressive forces. As a state, liberation is a condition in which oppressive

forces no longer exert their dominion over a person or a group. Liberation may be from psychological and/or

political influences. Building on Fromm's dual conception of 'freedom from'

and 'freedom to' (1965), liberation is the process of overcoming internal and

external sources of oppression (freedom from) and pursuing well-being (freedom

to). Liberation from social oppression entails, for example, emancipation from

class exploitation, gender domination and ethnic discrimination. Freedom from

internal and psychological sources includes overcoming fears, obsessions or

other psychological phenomena that interfere with a person's subjective

experience of well-being. Liberation to pursue well-being, in turn, refers to

the process of meeting personal, relational and collective needs.

The

process of liberation is analogous to Freire's concept of conscientization,

according to which marginalized populations begin to gain awareness of

oppressive forces in their lives and of their own ability to overcome

domination (Freire,1972). This awareness is likely to develop in stages (Watts,

Griffith & Abdul-Adil, 1999). Through various processes, people begin to

realize that they are the subject of oppressive regulations. The first

realization may happen as a result of therapy, participation in a social

movement or readings. Next, people may connect with others experiencing similar

circumstances and gain an appreciation for the external forces pressing down on

them. Some individuals will go on to liberate themselves from oppressive

relationships or psychological dynamics such as fears and phobias, whereas

others will join social movements to fight for political justice (Bourdieu,

1998). While a fuller exploration of interventions will be given in Chapters

8,9 and 10, we offer below some parameters for intervention at different levels

of analysis.

Individual and Group Interventions

Research

on the process of empowerment shows that individuals rarely engage in emancipator

actions until they have gained considerable awareness of their own oppression

and have enjoyed support from other community members (Kieffer, 1984; Lord

& Hutchinson, 1993). Consequently, the task of overcoming oppression should

start with a process of interpersonal support, mentoring and psycho political

education. It is through this kind of support and education that people

experience consciousness-raising (Hollander, 1997; Watts et al., 1999).

The

preferred way to contribute to the liberation of oppressed people is through

partnerships and solidarity. This means that we approach others in an attempt

to work with them and learn from them at the same time as we contribute to

their cause (Nelson, Ochocka, Griffin & Lord, 1998; Nelson, Prilleltensky

& MacGillivary, 2001). The three community mental health organizations

studied by Nelson et al. (2001b) dedicated themselves to empowering people with

psychiatric problems.

At

their best, these organizations provided support and empowerment to their

members, affording them voice and choice in the selection of treatment, caring

and compassion, and access to valued services and resources. Similarly, action

groups studied by Speer and colleagues offered citizens better resources such as

services and housing, but connectedness at the same time (Speer & Hughey,

1995; Speer et al., 1995). In both sets of studies, the groups acted as

communities of support and communities of power.

Community and Societal Interventions

Joining

strategic social movements is perhaps the most powerful step that citizens can

take to transform unacceptable social conditions. In some cases these will be

global movements, in others they may be regional or community-based coalitions.

In North America community-building efforts have proved useful in bringing

people together to fight poverty. Snow (1995) claims that 'community-building

can enable the underprivileged to create power through collective action' (p.

185), while McNeely (1999) reports that 'community building strategies can make

a significant difference. There is now evidence of many cases where the

residents of poor communities have dramatically changed their circumstances by

organizing to assume responsibility for their own destiny' (p. 742). McNeely lists

community participation, strategic planning, and focused and local

interventions as being central to success. Similar initiatives have taken place

in Europe to address the multifaceted problems faced by residents in large

public housing estates. Community organizing helped many poor neighborhoods

throughout the UK to demand and receive improved social services such as

health, policing and welfare (Power, 1996).

In

their research of block booster projects in New York, Perkins and Long (2002)

found that sense of community and conununitarianism predicted collective

efficacy, which is encouraging because collective efficacy may be a precursor

of social action. A similar and encouraging result was reported by Saegert and

Winkel (1996) who found that social capital increased empowerment and voting behavior

at the group level.

These

interventions work at the personal, relational and collective levels at the

same time. By participating in social-action groups, citizens feel empowered

while they develop bonds of solidarity, a phenomenon that is particularly

prominent in women-led organizations (Gittell, Ortega-Bustamante & Steffy,

2000; hooks, 2002). The feelings of

empowerment and connection contribute to personal and relational well-being;

whereas the tangible outcomes in the form of enhanced services and quality of

life contribute to collective well-being. In comparing two social action

groups, Speer and colleagues found that members of the organization that

invested more in interpersonal connections reported their group to be 'more

intimate and less controlling. They also reported more frequent overall

interpersonal contact and more frequent interaction outside organizing events.

Members of the community based organization also reported greater levels of psychological

empowerment' (Speer et al.,1995, p. 70). Their research illustrates how an

organization can promote empowerment and community at the same time.

What Are Some of the Risks and Limitations

of Community and Power?

Community

Social

capital may be used to increase bonding or bridging. Whereas the former refers to exclusive ties

within a group, the latter refers to connections across groups.

Country

clubs, ethnic associations, farmers' associations and men's groups increase

bonding. Coalitions, interfaith organizations and service groups enhance

bridging (Agnitsch, Flora & Ryan, 2001). There is a risk of bonding

overshadowing the need for bridging. If every group in society was interested

only in what is good for its own members, there would be little or no

cooperation across groups. Bridging is a necessity of every society. It is a

basic requirement of a respectful and inclusive society. However, there are

examples of groups investing in bonding to prevent bridging. Classic examples

include the Ku Klux Klan and movements that support ethnic cleansing.

If

bonding leads to preoccupation with one's own well-being and the neglect of

others', we see a problem. The problem is even greater if social capital is

used to promote unjust policies or discrimination. 'Networks and the associated

norms of reciprocity are generally good for those inside the network, but the

external effects of social capital are by no means always positive' (Putnam,

2000, p. 21). Proponents of mindsets such as NIMBY (not in my backyard) and

coalitions of elite businesses exploit their power and connections to achieve

goals that are in direct opposition to the values of CP. 'Social capital, in

short, can be directed toward malevolent, antisocial purposes, just like any

other form of social capital .... Therefore it is important to ask how the

positive consequences of social capital — mutual support, cooperation, trust,

institutional effectiveness — can be maximized and the negative manifestations

— sectarianism, ethnocentrism, corruption — minimized' (Putnam, 2000, p. 22).

Another

serious risk of the current discourse on social capital is its potential

deflection of systemic sources of oppression, inequality and domination. There

is a distinct possibility that social capital may become the preferred tool of

governments to work on social problems because it puts the burden of

responsibility back onto the community (Blakeley, 2002; Perkins, Hughey &

Speer, 2002). We believe that communities should become involved in solving

their own problems. But that is part of

the solution, not the whole solution. No

amount of talk about social support can negate the fact that inequality exists

and that it is a major source of suffering for vulnerable populations. Social

support can buffer some of the effects of inequality, but it would be ironic if

it was used to support the same system that creates so much social

fragmentation and isolation. Hence, we caution against social capital becoming

the new slogan of governments. Furthermore, we call on people to create bonds

of solidarity to enhance, not diminish, political action against injustice. We

concur with Perkins et al. who claim that 'excessive concern for social

cohesion undermines the ability to confront or engage in necessary conflict and

thus disempowers.' (2002, p. 33).

Power

Too

much power in the wrong hands and too little power in the right hands are two

problems associated with power. Of course, we don't always know which are the

`wrong hands' and which are the 'right hands.' But, in principle, we know that

certain groups are clearly over-empowered. In 2002, newspapers and magazines

worldwide were decrying the unrestrained power of corporate executives. The

collapse of corporations such as Enron and Worldcom, due in part to the

unrestrained power of chief executive officers and their ability to doctor the

books, left thousands of people with no pension plans and thousands of others

with no life savings (for example, Gibbs,2002). We don't want to give more

power to corrupted corporate leaders, nor, for that matter, to racist

demagogues or unreformed sexists.

Far

too often, not enough power gets into the hands of the marginalized. A number

of barriers stand in the way of the disempowered (Gaventa & Cornwall, 2001; Serrano-Garcia &

Lopez Sanchez,1994; Speer & Hughey,1995; Speer et al., 1995). Superior

bargaining resources are the first instrument of power in the hands of the

powerful. Those with resources to pay lawyers and send their children to elite

schools have more access to power than those with fewer resources. In the case

of a dispute, those with the lawyers, the money and the connections can

outweigh the position of the disadvantaged.

By

setting agendas and defining issues in a particular way, power is also

exercised by excluding issues such as inequality, privilege, oppression,

corruption and power differentials from discussions and public debate. The

third barrier to power and participation is defining issues in such a way that

people do not realize that power is being taken away from them. Callers to the

Suzie Orman show (see Box 5.2) are being robbed of power when they believe that

their 'net-worth is a reflection of their self-worth'. They are buying into

myths and cultural messages that prevent them from fighting injustice. Instead,

they are told to go to therapy to improve their selfesteem. This is a forceful

way to deny people the power of political and economic literacy (Bourdieu,

1990, 1998; Bourdieu & Passeron, 1977).

Finally,

we caution against covering the whole human experience with a blanket of power.

Power is vitally important in fostering well-being and liberation. Moreover, it

is ever present in relationships, organizations and communities. But we want to

think that there are spaces in human relations where power differentials are

minimized, where people feel solidarity with others, where empathy outweighs

personal interests and where love and communion are more important than

narcissism (Craig & Craig, 1979; Dokecki, Newbrough, & O'Gorman, 2001;

hooks, 2000, 2002). The complementary risk is that we fail to see power where

power is present, for masking power is perhaps one of the gravest risks in the

pursuit of wellbeing and liberation.

In

this chapter we explored the concepts of community and power. These two

concepts are the root of sense of community and empowerment, both of which have

been hailed as defining metaphors for CP. We considered geographical and

relational communities and explored sense of community and social capital. The

research demonstrates that cohesive communities achieve better rates of health,

education, tolerance and safety than fragmented ones.

The

benefits of social support extend beyond the individual. Social networks

improve outcomes for children, adults and for the community as a whole. While the

positive outcomes of cohesion and social capital are many, it's important to

remember that group unity can be used to exclude 'others'. It is equally

important to keep in mind that social capital and the call for community may be

used to excuse governments from investing in public resources (Blakeley,2002).

In other words, community and social capital may be used to deflect

responsibility from governments.

Whereas

bridging and bonding are desirable qualities of healthy communities, they can

restrict opportunities for challenging power structures and for engaging in

productive conflict. Although social capital can contribute to health and

welfare, it can also depoliticize issues of well-being and oppression (Perkins

et al., 2002).

The

ability of communities to promote well-being and liberation is linked to the

power of the group to demand rights, services and resources. We explored the

concept of power and noted its multifaceted nature and applications. For us,

power is a combination of ability and opportunity. In other words, power is not

just a psychological state of mind, but a reflection of the opportunities

presented to individuals by the psychosocial and material environment in which

they live. Of particular interest to us is the potential of power to promote

well-being, to cause or perpetuate oppression and to pursue liberation.

Personal empowerment has to be complemented by collective actions (Cooke,

2002). We identified three main barriers to power, based on the ability of the

powerful to (a) use resources to reward and punish behaviour in line with their

interests, (b) set agendas, and (c) create cultural myths and ideologies that

perpetuate the status quo. We noted that our work is challenged by the fact

that it is not always clear who needs more power and who needs to be

disempowered. Knowledge of the values, the context and the various interests at

play is the best antidote to dogmatism. We can see too much power in certain

places and not enough of it in others. Both are serious risks, for we don't

want to be oblivious to power, nor do we want to project it where it doesn't

belong.

COMMENTARY: Parents Involved in Schools: A Story of

Community and Power Paul Speer.

Several years

ago my wife Bettie became an active participant in the Parent Teacher

Organization (PTO) of our children's school. One of the tasks she undertook was

to develop a school handbook that provided important information for school

families: school rules and procedures, parking at the school, procedures for

snow days, where to go with questions and so on. In preparing the handbook,

Bettie drafted a mission or role statement of the PTO vis-à-vis the school. The

statement asserted that the role of the PTO was to support and enhance the

educational opportunities in the school, to facilitate exchange of information

between parents and teachers and to serve as a parents' liaison with the school

administration when parents raised concerns. At a meeting of PTO officers and

the school principal, the group balked at the point in the mission statement

asserting that the organization could serve as a mechanism for addressing

parental concerns about the school.

The principal

felt this was not the role of the PTO, some officers voiced the view that the

PTO's role was exclusively as a 'support' organization and other officers

complained that a statement regarding 'parental concerns' was 'too

controversial'.

Bettie urged

that the PTO served as a mechanism by which parents could raise concerns,

particularly to the administration, as no such mechanism existed for the

school. She was corrected by other parents who, with the nodding approval of

the principal, revealed that if a parent had a concern about school policies or

procedures, he or she should bring it up with the principal.

Power is Pervasive

Betties

experience reveals many of the power dynamics discussed in this chapter. For

me, some of the most important are how unconscious forces and ideologies

operate to reinforce the status quo - to the detriment of our values for

justice and equality. When the idea that there should be a mechanism for

addressing concerns gets defined by

parents - not the principal - as controversial, it not only contradicts the

very nature of a democratic process but reveals a form of self-imposed

regulation

that represents the hallmark of power (Haugaard, 1997). A common myth is that

individuals susceptible to power, persuasion and manipulation are generally not

well educated.

Interestingly,

the parents involved in the PTO were mostly very well educated - I believe all

had college degrees and several had post-graduate degrees. But, as this chapter

points out, one of the most important aspects of power is the ability to

distort knowledge - to shape what people know or how they view the world. This

mechanism is not bound by education, race, class or gender. How do we come to

'know' that PTOs are for fundraising and not for participating in school

governance?

How did this

understanding come about for the well-educated group of parents in this

organizati on? M important contribution of this chapter is the explicit

attention it provides to the unconscious mechanisms through which power is

exercised.

These

mechanisms are under-appreciated and largely ignored by psychologists, but

nevertheless pervasive in community contexts.

Blending Power and Community

Perhaps the

greatest insight of this chapter is the blending of the concepts of power and

community.

In my

experience with community organizing, the development of social power comes

only through gathering the strength of many individuals into a unified

collective. To build a unified collective requires tremendous effort and time,

but more fundamentally, it requires (in a non-economic context) building a

sense of community that can operate within and across groups, in what the field

of social capital calls both 'bridging' and 'bonding' forms of social capital.

The conscious development of a collective with a strong sense of community will

not always be successful - it depends on the context of that community and the experiences,

interests and values of the individuals within that community. Organizing is

about learning and understanding the experiences and interests of a group of

individuals. To develop such knowledge and understanding requires building

relationships with numerous individuals. In community organizing, one of the

key organizing principles is: power flows through relationships (Speer &

Hughey, 1995).

This process

does not seem too difficult, but putting this principle into practice requires

skill, commitment, time and a passion for justice. I've witnessed many failed

attempts to organize communities and the reasons for these failures are many.

Often, organizing efforts identify the issue to be organized a priori -

organizers attempt to form groups working on substance abuse or housing or

education. Organizing in such a way undermines the process of listening, thus

limiting an understanding of the interests and values of individuals in a

community. When outsiders, be they organizers, experts or funders, define in

advance the issues for a community, the result is a weakened organization and

an organizing process that resembles an exercise in manipulation. Most

importantly, the activity produced in 'issue-defined' organizing efforts

generally has little sustainability - and thus little power.

Mother common

shortcoming to community work when issues of community and power are not viewed

together is that participation is encouraged as an end in itself. In many

contexts, we view citizen participation as essential for democracy and a key

method of building community and developing empowerment. But what of Bettie's

experience in the PTO? Did participation there build power or cultivate

community? These questions are not easily answered - they are very complex. A

particular strength of this chapter is that

it communicates some of the

complexity and nuances involved in community work and issues of power. Too

often community psychologists oversimplify these issues.

Citizen

participation, for example, is generally held to be a 'good thing'. I am not

disputing this, but I would suggest that powerful interests have shaped many of

the settings and niches in which we can participate and, as a result, our

participation has been defined in very narrow, limited ways. At the PTO, Bettie

participated in fundraising to bring educational opportunities to the school

(dancers, rappers, puppeteers and so on) but the educated, involved and

resourced parents kept participation focused on fundraising and away from

deeper issues of equity and justice in that school (tensions in our school

existed around 'well-connected' parents selecting their children's teacher thus

producing 'designer classrooms' and segregated seating in the school lunch room

due to seating assignments based on whether kids were part of the free or